New Directions

The Tribar Signs in RIL Inscriptions

AUTHORS: Samir Oujhain and Abdellah El Haloui

The Tribar Signs in RIL Inscriptions

Samir Oujhain and Abdellah El Haloui

Cadi Ayyad University

Abstract: This article presents a multidisciplinary analysis, integrating comparative linguistics, epigraphy, and philology, to re-evaluate the tribars found in Eastern Libyco-Amazigh (LA) inscriptions within Chabot’s “Recueil des inscriptions libyques” (RIL). Challenging the prevailing assumption of tribar interchangeability, this study distinguishes between horizontal and vertical tribars, proposing distinct phonetic values. Through a multidisciplinary approach, it argues that the horizontal tribar consistently functions either as an unknown suffix or a final vowel. Conversely, the vertical tribar is identified as a variant of /z/, likely /ʒ/, with its Punic correspondence to /h/ attributed to phonological adaptation. This article also explores the morphological and epigraphic features of the tribars, particularly the feminine prefix (T-) and the systematic distribution of the tribar cluster (VH), to support distinct phonetic values. By addressing counterarguments and acknowledging data limitations, this study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of RIL inscriptions, and illuminating the phonetic values and potential grammatical functions of these graphemes.

Keywords: comparative linguistics, epigraphy, philology, RIL, horizontal and vertical tribars, phonological adaptation, phonetic values

Introduction

This article analyzes the problematic issue of the phonetic values of the tribars in Eastern Libyco-Amazigh (LA) inscriptions. I closely study the controversial opinions expressed by many scholars to address the puzzling issue of the phonetic value of the tribars in LA Eastern inscriptions. Therefore, this article examines the linguistic and epigraphic features of the horizontal and vertical tribars in the inscriptions documented by Chabot (1941) in his corpus, RIL.[1]

In RIL inscriptions, one might recognize that some of these inscriptions are epitaphs and dedications which include the personal name of the deceased, his or her parental name as well as some intricately complex segments such as NCFH, NBYBH, NNBYH, NNDRMH, NMRSH, MSKRH, MNKDH, MDYTH, etc.[2] Chabot (1941) assigns both the vertical and horizontal tribars the sound (H) though the evidence for this assignment is limited and unjustified. Yet, I sometimes use the phonetic value (H) to refer to the tribars for a descriptive reason.

Three main features characterize those intricately complex segments: recurrence, inter-occurrence, and co-existence with the tribars (H). Therefore, I will call these recurrently co-occurring segments (Segment-Hs) because they are usually followed by the sign (H). The Segment-H cannot be a personal name for at least two reasons. Firstly, the well-attested word (W-) meaning “son of” never precedes it; Chabot (1941) uses (U) instead. I call this reason W-Incompatibility. Secondly, more than one Segment-H can co-occur frequently in the same inscription, that is, one can find more than two segments in the same inscription and sometimes in the same line. I call this reason Compatible Coexistence. Therefore, the Segment-H could be anything but an onomastic word.

While tribars tail all Segment-Hs, they also tail some parental names (W-name) (RIL 3, 4, 11, 85, 126, 203, 210, 223, 225, 288, 290, 293, 441, 295, 599, 634, 1033, 1058, etc.). This entails that tribars are not exclusively used with Segment-Hs. In addition, tribars rarely co-occur with the personal names (RIL 72, 85, 558, 723).

To sum up, tribars are very important graphemes in RIL inscriptions because they are employed regularly together with Segment-Hs and some onomastic words. Chabot (1941) considers the horizontal and vertical tribars to be identical and assigns them the laryngeal sound (H) /h/.

Background

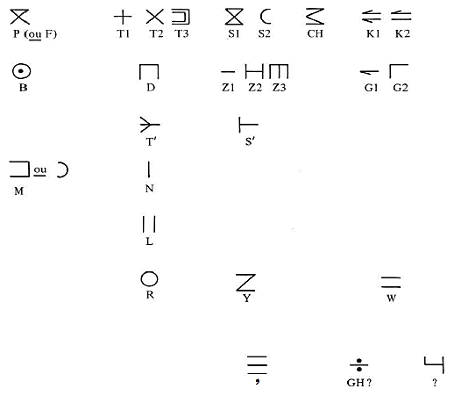

In the forties, Chabot (1941) identifies the phonetic values of the RIL inscriptions and their equivalents in Punic as follows:

Table 1: Chabot’s Phonetic Values in RIL (1941)

These phonetic assignments have the following limitations as far as the LA tribars are concerned. Firstly, Chabot does not use the horizontal tribar, but he only uses the vertical one though there is no evidence to assume that the horizontal and vertical tribars are employed interchangeably. Secondly, he uses the laryngeal sound (H) to represent four different Punic signs. These signs have different sounds in Punic, and only one Punic letter that stands for the laryngeal sound (H). Thirdly, he assigns the LA sign (÷) the Punic sound (Q) though this correspondence is not attested in any bilingual inscription, namely in Libyco-Punic (LP) texts. Due to these limitations, he assigns 24 different sounds to 28 LA signs though Amazigh phonology might have other phonemes and allophones.

In the seventies, Galand (1973) argued that almost all LA signs in RIL1 and RIL2 were decipherable thanks to the Punic equivalent sounds employed in personal names. These phonetic assignments also depended on previous studies about LA inscriptions (cf. Chabot, 1940 - Février, 1956 - Rössler, 1958).

However, Galand (1973) stated that the Punic transcription lacked the horizontal tribar ≡ because it was not used in any personal name in addition to two other LA signs: the sign (÷) and the horizontal sign (h). Therefore, it was difficult to identify its phonetic value depending on RIL1 and RIL2, but he assumed that it was a final vowel (’) rather than an ancient laryngeal (H) (cf. Rössler, 1958).

Table 2: Galand’s Phonetic Values of LA Signs in RIL1 and RIL2 (1973)

“Cependant, le parallélisme onomastico-linguistique que nous avons établi dans le cadre de notre thèse de doctorat a prouvé que le « tribarre » servait à noter à la fois” (Sfaxi, 2022).

Recently, Sfaxi (2022) observed that onomastic-linguistic parallelism proved that the “tribar” was used to note three sounds at the same time: (i) the vowels (a) and (o): (RIL280, 252, 289, 324, 325, 145), (ii) the semi-vowel (au): (RIL402, 475, 496, 500, 811), and (iii) suffixes of foreign names: (RIL 85, 314) (pp. 110, 111). Then, she stated that the tribar and the (w) sound should represent the final semi-vowel (au) or (aw) “Partant de ce constat, le ‘tribarre’ et le w devraient servir à noter la semi-voyelle finale au/aw” (Sfaxi, 2022, p. 111).

Certainly, there are different opinions about the phonetic values of the vertical and the horizontal tribars (ⵏⵏⵏ and ≡) in LA studies. Bearing in mind, most of these researchers do not distinguish between the vertical and horizontal tribars; they use only one sign in their phonetic tables (ⵏⵏⵏ and ≡) because they assign both tribars identical sounds. The following table introduces a number of sounds suggested to represent the tribars by four researchers (cf. Kossmann, 2020, p. 878).

| Chabot | H | Laryngeal |

| Rössler | ʔ | Glottal |

| Pichler | ʔ | Glottal |

| Kerr | Vowel | Vowel |

Table 3: Phonetic value of the sign ≡

In addition, the subsequent table introduces a several sounds assumed to represent the tribars by 13 researchers (Pichler, 2007, p. 78);

| Chabot | H | Laryngeal |

| Prasse | H | |

| Rössler | Laryngeal | |

| Chaker | Velar | Velar |

| Meinhof | g/Q | |

| Mukarowsky | GH/Q | |

| Mauny, Marcy | I | Vowel |

| Basset | I | |

| Delgado | Y | |

| Galand | final vowel | |

| Lafuente | punctuation/ final vowel | |

| Fevrier | mater lectionis3 |

Table 4: Phonetic Value of the Sign ⵏⵏⵏ

Many RIL inscriptions use the tribars in the final position, that is, at the end of a line or at the end of a recurrent segment such as MSKR-H, MNKD-H etc. Pichler (2007, p. 78) states that RIL inscriptions also include a few examples for (ⵏⵏⵏ) in initial position – six according to Lafuente (1957, p. 388) – and about a hundred examples for medial position. In addition, a few RIL inscriptions use the tribars at the middle of words (i.e. RIL 31, 54, 76, 208, 209, 210).

Moreover, Chabot (1941) states that the tribars are found in the initial position of these inscriptions: (RIL 591, 737, 798, 161, 1000, 632, 807, 274)[4]. The following table distinguishes between the vertical and horizontal tribars used in the initial position;

| Vertical | RIL161 (WHLT) (w– “son of”) |

RIL632 (HNH) | RIL274 (HZ?TH) | RIL591 (HDLW) According to Masqueray |

| Horizontal | RIL591 (HDLW) According to Reboud | |||

Table 3: Vertical and Horizontal Tribars in Initial Position

Accordingly, the horizontal and vertical tribars have three phonetic values in the LA literature; a laryngeal, a velar and a vowel. Comparing LA inscriptions with their Punic and Latin equivalents provides crucial clues, but inconsistencies and limitations still exist. The purpose of this article is to analyze these inconsistencies and limitations by means of integrating diverse methodological approaches.

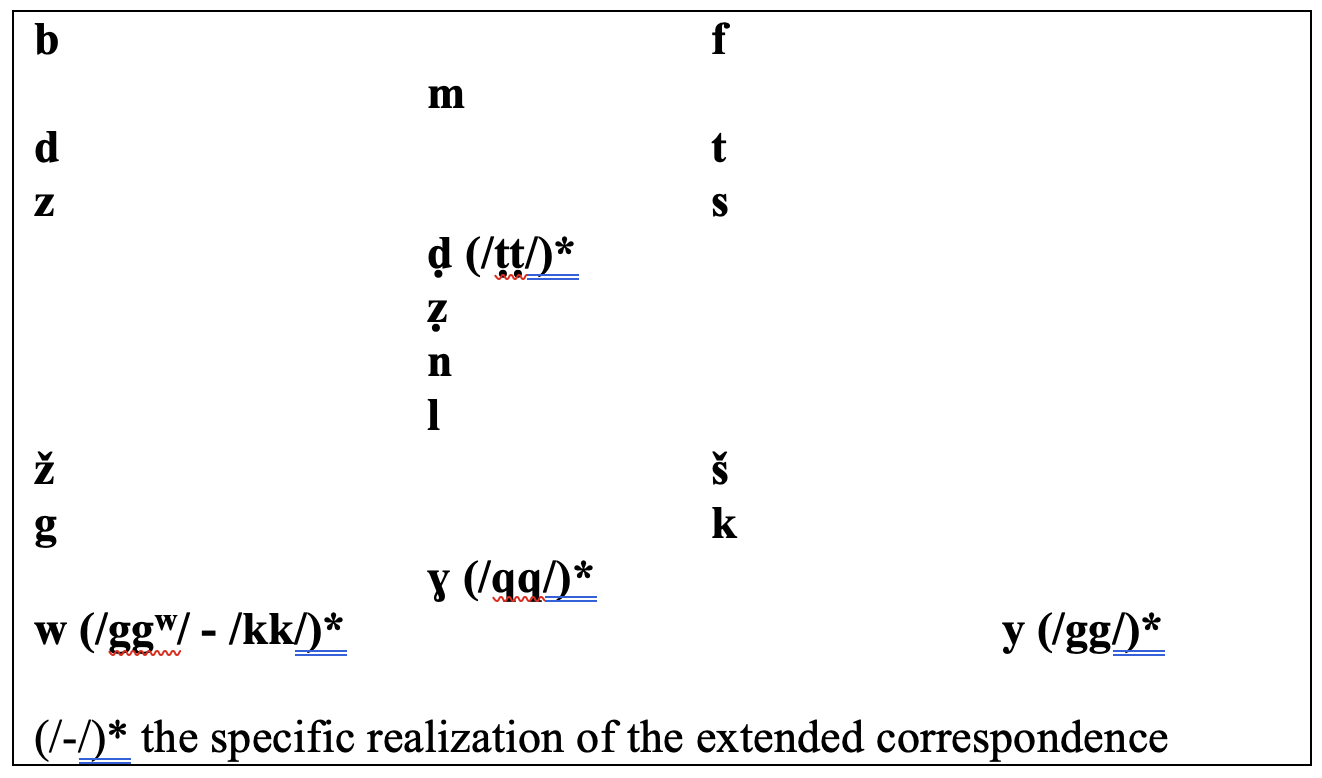

The following table illustrates the common phonological system among all Modern Amazigh (MA) dialects in North Africa. It shows that MA dialects share 18 consonants, including the semi-vowels (w) and (y) (Chaker, 2015, p. 22).

Table 4: The Common Phonological System in Amazigh

If the common phonological system of Amazigh is compared to Galand’s Phonetic Values of LA signs in Dougga (Galand, 1973), one might realize that the tribars, and likely other unknown signs, could be the following sounds: the sibilant /ʒ/ or the velar /q/. These sounds are common in Amazigh dialects, but their letters are not found in RIL inscriptions. Therefore, I hypothesize that these two sounds constitutes gaps in the phonological system of RIL inscriptions.

In this article, I argue that various sound values hinder the assignment of an appropriate sound value to the tribars because there is no distinction between the vertical and horizontal tribars. This distinction would enable the assignment of limited sound values to the tribars. For example, one tribar could be a vowel sound, and the other one could be a consonant sound, or one could be a laryngeal sound and the other one a velar sound.

Despite extensive research, the phonetic values of both the vertical and horizontal tribars might remain uncertain, which hinders progress in the interpretation of LA Eastern inscriptions. The vertical and horizontal tribars are not identical because not only they co-exist in some inscriptions but also their linguistic and epigraphic features are distinguishable.

Methodology

The source material for this study is the RIL compiled by Chabot in (1941). This corpus provides a substantial collection of LA inscriptions containing the problematic tribar signs. The selection of specific inscriptions for detailed analysis is guided by the presence of tribars, the availability of corresponding Punic or Latin texts (in bilingual inscriptions), and the occurrence of recurrent segments associated with the tribars. Though the entire RIL corpus serves as source, the analysis focuses on specific examples that precisely demonstrate the issues under investigation, namely biscripts (bilingual inscriptions).

This article uses both the quantitative and qualitative approaches to study the phonetic values of the tribars in Eastern LA inscriptions. The methodology employed is primarily comparative linguistic analysis, supplemented by epigraphic examination and philological interpretation. This multidisciplinary methodology is designed to investigate the uncertain phonetic values of the tribars and their impact on the decipherment of LA inscriptions in RIL.

Comparative linguistics involves comparing LA inscriptions with their Punic and Latin counterparts to identify potential correspondences. This comparison is crucial for attempting to determine the phonetic values of the tribars. The analysis considers not only direct letter-by-letter correspondences but also broader patterns of sound change and the limitations of using alphabetic scripts (Punic, Latin) to represent a potentially different sound system, which is the LA script.

Epigraphic examination aims to examine the physical characteristics of the tribars themselves, including the form and orientation of the signs, their placement within the inscriptions, and their relationship to other signs. This epigraphic analysis enables to contextualize the linguistic analysis and to identify potential ambiguities or inconsistencies in the script.

Philological interpretation involves the decoding of the inscriptions within their historical and cultural context. It considers the types of inscriptions (e.g. epitaphs, dedications), the recurrent segments that appear in them, and the potential meanings of these segments. The analysis also considers the limitations of relying on bilingual inscriptions, recognizing that the Punic and Latin versions may not always provide a complete or accurate representation of the LA text. The philological interpretation aims to integrate the linguistic and epigraphic evidence to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the inscriptions.

My philological interpretations are based on a lexical analysis approach; namely, Haddadou’s methodology in classifying common Amazigh vocabulary (cf. Haddadou, 2007). He argues that Amazigh dialects should be grouped into five zones; if one word is attested in two distinctly remote zones, it belongs to the common lexicon of Amazigh (Haddadou, 2007, p. 16). He borrowed the term Pan-Berber from Chaker (1996). This term considers that cognacy in at least two different zones suggests that those words belong to Ancient Amazigh (Haddadou, 2007, p. 16). I will also use the term Pan-Amazigh to accentuate not only potential common lexicon among MA dialects and the LA dialect used in RIL but also the potential phonological alternations between LA dialect and Pan-Amazigh.

This study critically evaluates the work of previous scholars, highlighting the limitations and inconsistencies of their approaches. This critical engagement with existing scholarship helps refine the research questions and develop alternative explanations.

It is important, however, to note that this methodology, while comprehensive, is subject to the limitations of the available data. The lack of extensive bilingual texts and the uncertainties surrounding the tribars and Segment-Hs pose significant challenges to the decoding process. However, by integrating these different components of inquiry, the study aims to make a valuable contribution to our understanding of the puzzling tribars in the Eastern LA inscriptions.

A Multidisciplinary Approach to Study the Tribars

1- The Horizontal Tribar

In this section, I argue that the horizontal tribar does not correspond to any letter in bilingual inscriptions, and it occurs only in the final position of the LA words attested in Dougga inscriptions. To examine the reliability of this argument, I carefully analyze the data observed in the biscripts containing the horizontal tribars depending on epigraphic and philological comparisons.

The horizontal tribar ≡ is used in many Dougga inscriptions (RIL1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). RIL1 and RIL2 are important inscriptions because they are bilingual LA inscriptions. The horizontal tribar is used twice in RIL1; it is found in line 7 in the first word (nšqrH) and the third word (nzlH). It is employed three times in RIL2; it is found in line 6 in the second word (s2bs2ndH) and in line 7 in the second word (sysH) as well (cf. Galand, 1973).

| RIL 1 | Meaning | Punic translation |

Position of (H) | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Line 6 (2nd word) |

nšqr-H |

of wood (638 ƔṚ) |

šyr | Final |

(H) is not part of the root ƔṚ |

|

Line 7 (2nd word) |

nzl-H |

of iron (894 WZL) |

šbrzl | Final |

(H) is not part of the root WZL |

Table 5: The Horizontal Tribars in RIL1

In RIL 1, Krahmalkov translates the Punic text HBNM S’BNM … HHRSM SYR … HNSKM SBRZL as follows: “the builders of (buildings) of stone … the makers of (objects) of wood … the casters of (objects) of iron” (2001, p. 105). Undoubtedly, the Punic phrase HHRSM SYR “the makers of (objects) of wood” is a translation of the LA phrase NBBN N-ŠQRH that literally means “the cutters of wood” in Pan-Amazigh. The recurrent word NBBN might be derived from the root BY 064 meaning “to cut”, and the word N is a preposition meaning “of” (538 N) (Haddadou, 2007). Moreover, the subsequent Punic phrase HNSKM SBRZL meaning “the casters of (objects) of iron” also corresponds to the LA phrase NBBN N-ZLH that literally means “the cutters of iron” in Pan-Amazigh as well.

Of course, the tribar is never used in any potential personal names that are recognizable in RIL1 and RIL2 because it only occurs in non-onomastic words. Obviously, it is not part of the roots ŠQR “wood” and ZL “iron” in Pan-Amazigh.

As I have mentioned earlier, RIL 2 contains three words (or phrases) ending with the horizontal tribars. The following table demonstrates the Punic lines and their LA equivalents found in RIL2 depending on onomastic correspondences. Unfortunately, the tribars are employed only in non-onomastic words.

| Punic lines | LA corresponding lines |

|---|---|

| 1– tmqdšz-bnh-bʕlh-tbgg-lmsnsn-hmmlkt-bngʕyy-hmmlkt-bnzllsn-hšft- bštṣsrš […] | skn-tbgg- bnyfš[?]- msnsn- gldt- wg̣yy- gldt-wzllsn-šft - s2bs2ndH-sgdt-sysH- gld |

| 2– mkwsn- bšt-šft-hmmlkt-bnčfsn- hmmlkt-rbtm't-šnḳ-bnbny-wšft-bnngm- bntnkw | mkwsn- šft- gldt- wfšn- gldt- mwsnH-šnḳ-wbny-wšnk-dšft-wm[…] - wtnkw |

Table 6: The Horizontal Tribars in RIL2 and Their Corresponding Phrases in Punic

Moreover, the interpretation of these words (or phrases) is complex in comparison to RIL1 because the Punic translations are not direct, that is, it is difficult to recognize semantic correspondences between the LA words and the Punic counterparts. The difficulty is due to a certain lacuna in the Punic lines.

In the following table, I analyze the LA words containing the tribars and their potential equivalents in Punic depending on philological analysis.

| RIL 2 | Meaning | Punic translation |

Position of (H) | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Line 7 (1st word) |

s2bs2n-dH |

years-which (880WS) |

bšt-ʕsr "in the year ten" |

Final |

(H) is not part of the root WS |

|

Line 7 (3rd word) |

sys-H |

to have authority/ to rule (914YS) |

[š…] | Final |

(H) is not part of the root YS |

|

Line 7 (5th word) |

mwsn-H |

sage (797SN) |

rbtm’t "chief of the hundred" |

Final |

(H) is not part of the root SN |

Table 7: A Philological Analysis of the Phrases/ Words Containing the Tribars in RIL2

If this analysis is correct, the interpretation of these LA phrases might be “the numerous years in which he ruled”:

S2BS2N-DH: “the years which”

SGDT: “numerous”

SYSH: “to have authority/ to rule”

It is clear that the Punic phrase BŠT ʕSR “in the year ten” corresponds with the LA phrase S2BS2NDH because LA translates BŠT as S2BS2 (or S2BS2N) meaning “year(s)” in Pan-Amazigh. The word ʕSR “ten” is not translated in the LA lines because the phrase S2BS2N-DH does not contain the root MRW meaning “ten” in Pan-Amazigh, but it might mean “in the years” especially that DH might mean “which” in Pan-Amazigh. For example, the relative pronoun (iḏ) means “which” in Zenaga (Faidherbe, 1877, p. 11), and the relative pronoun (dda) also means “which” in Tashelhit (Justinard, 1914, p. 29); Zenaga and Tashelhit belong to different zones in Pan-Amazigh.

The subsequent LA word SGDT might be derived from the root 295GT meaning “large quantity, numerous” (Haddadou, 2007), and it might be an indirect translation of the Punic word ʕSR meaning “ten.”

Syntactically, the lack of agreement between the plural noun S2BS2N and the singular adjective SGDT might make this interpretation uncertain. Yet the lack of agreement makes any other potential interpretation incomplete. Considering the suffix (-N) as a preposition, namely “of”, is not only ungrammatical but also meaningless. Therefore, SGDT could only mean “numerous”.

Unfortunately, there is no corresponding Punic word to the LA word SYSH except the fragment Š[…]. However, the root YS, in Pan-Amazigh, means “to make efforts, prestige, authority” (914 YS) (Haddadou, 2007), and it might be connected to SYSH. Thus, SYSH might be a verb meaning “to have authority/ to rule”; the use of such a verb is expected in a royal funerary context.

Chaker (1986) states that Chabot translated MWSNH as “chief of the hundred” (cf. RIL2). He emphasizes that MWSNH is not (and does not contain) a number (100) in Amazigh. The Punic title is in any case an adaptation and not a literal translation: MWSNH can not be analyzed as “chief of the hundred” (p. 3). Moreover, Chaker (1986) hesitates to translate the LA MWSNH as “President of the Council of a Hundred” (cf. Février, 1956) because such a translation is based entirely on the precise value of the Punic term and implies as a priori “Punicis” as to the municipal organization of the Libyans (p. 3).

Therefore, Chaker (1986) argues that nothing excludes the possibility that the traditional Phoenician-Punic title was applied to Libyan realities and practices quite different from those of the Phoenician world. Hence, he suggests that LA MWSNH might be derived from the Amazigh root WSN meaning “to know”, and MWSNH might mean “sage”.

Chaker (1986) could not find any direct semantic correlation between the Punic word (RBT M’T) and the LA word (MWSNH). Therefore, he suggests that the LA word (MWSNH) might be derived from the Amazigh root (SN) meaning “to know”. He also employs Chabot’s phonetic value to the tribars (H), and he does not provide any explanation to the reason behind using this unusual sound at the end of the root (SN).

Correspondingly, the horizontal tribar always occurs in the final position of the LA words whose roots do not contain the sound (H) or any other consonantal sound that might be represented by the horizontal tribar.

In addition, RIL 72 is another example where some LA lines correspond to Punic lines, namely the personal name (LA: IGKNH and P: IAGUAKAN) and the parental name (LA: WKNRDT and P: Son of KANRADAT). Chabot (1941) translates the Punic lines as follows:

«A Iaguâkan, fils de Kanradât, fils de Mesiâlan, ont été érigées ces pierres».

“To Iaguâkan, son of Kanradât, son of Mesiâlan, were erected these stones”.[5]

However, the Punic transcription is not done letter by letter because the Punic word (Iaguâkan) does not use the equivalent of the horizontal tribar ≡ in Line 1, IGKN(H).

Analogically to RIL1 and RIL2, I argue that the horizontal tribar might be a final vowel since it occurs in the final position of the personal name IGKN(H), and it is not used in the Punic transliteration IAGUAKAN.

Finally, RIL 451 is an important case where some LA lines correspond to the Punic lines, namely the personal name ZNN (LA) and ZANAN or [ŠANAN] (P), the parental name WYRNBT (LA) and Son of IARNABAT (P) and NMRSH (LA) and NMRSI in (P). In RIL 451, the non-onomastic word NMRS(H), where the horizontal tribar is employed, corresponds to the Punic word NMRS(I). Undoubtedly, the tribar is transliterated as the vowel /i/ in Punic. The transliteration of the non-onomastic word NMRS(H) may suggest that the latter might be a tribal name, or a common word between Punic and LA. Bearing in mind that the segment NMRS occurs at least five times in RIL.

Accordingly, RIL 451 shows that the horizontal tribar might be a final vowel, likely /i/. Yet, the correspondence of the tribar ≡ and the Punic sound (I) is not frequent; it only occurs once, namely in this inscription. Thus, the safest explanation is to consider that the horizontal tribar is not represented in Punic analogically to RIL1, RIL2, RIL72, and RIL451. Hence, it is wrong to assume that the equivalent of the horizontal tribar is (I) in Punic.

Based on these findings, the horizontal tribar ≡ does not correspond to any Punic letter in RIL1, RIL2, RIL72 and RIL451. I suggest two assumptions to explain the phonetic value of the horizontal tribars. Firstly, the horizontal tribar might be an unknown suffix that is not attested (or is no longer used) in Pan-Amazigh; it might be a suffix because it occurs in the final positions of potentially recognizable words, namely in Dougga inscriptions. Secondly, this sound might be a final vowel since (i) it always occurs in the final position of LA words, namely in Dougga inscriptions; and (ii) it is not found in the potential roots of those words in Pan-Amazigh.

The horizontal tribar occurs in LP inscriptions without any Punic transliteration. It is employed in both non-onomastic (RIL1, RIL2, RIL451) and onomastic words (RIL72) in final positions. The philological analysis of the non-onomastic words reveals that these words lack a final consonantal sound in Pan-Amazigh. Hence, one should deduce that the horizontal tribar might be an unknown suffix or a final vowel. Is the generalization of this argument systematic in other Dougga inscriptions and Segment-Hs?

In fact, the horizontal tribar occurs in the final position of twenty-one LA words in eight Dougga inscriptions (RIL1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 10); two of them are LP biscripts (RIL1 and 2). The table below provides the number of the systematic occurrences of these tribars in the final positions of potential words.

| RIL1 | RIL2 | RIL3 | RIL4 | RIL5 | RIL6 | RIL7 | RIL10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 |

| Total | 21 | |||||||

Table 8: The Frequency of the Final Horizontal Tribar in Dougga Inscriptions

In RIL, the horizontal tribar always occurs in the final position, except in four words at most (RIL187, 542, 591, 902). Such irregular inscriptions are infrequent, and they might be misleading because it is possible to confuse the clustered graphemes = − (LZ) or the other way around (ZL) with the horizontal tribar ≡.

Chabot (1941) uses two representations for (RIL187), and both use the horizontal tribar at the beginning. In RIL591, Reboud uses the horizontal tribar and Masqueray the vertical one; this uncertainty is a valuable reason to have doubt over the use of the horizontal tribar at the initial position in this inscription. Moreover, Chabot (1941) uses the cluster = − (LZ) instead of the horizontal tribar in RIL902. Hence, the use of the horizontal tribar in the initial position might simply be a cluster of the two confusing graphemes (ZL) or (LZ). Accordingly, the horizontal tribar could represent a final vowel in RIL inscriptions.

In conclusion, the horizontal tribar ≡ in LP inscriptions, particularly those from Dougga, presents a significant epigraphic and linguistic puzzle. Through a meticulous analysis of its occurrences in four LP biscripts and a critical evaluation of potential interpretations, this section demonstrates that the tribar does not correspond to a consistent Punic letter and predominantly appears in the final position of LA words. This observation strongly suggests that the tribar represents either an unknown suffix or a final vowel, rather than a consonantal sound belonging to the words’ roots.

While the precise phonetic or grammatical value remains uncertain, the evidence presented effectively challenges earlier assumptions and provides a foundation for future research. The consistent final positioning of the horizontal tribar, coupled with its absence in Punic equivalents, reinforces the argument that it serves a function unique to the LA language. Further investigation, potentially involving comparative linguistic studies and the examination of a broader corpus of LA inscriptions, is necessary to definitively answer the question of the horizontal tribar and to deepen our understanding of this sign in LA inscriptions.

2- The Vertical Tribar

In this section, I assume that the vertical tribar could be either a laryngeal or a velar because these two sounds are present in the common Amazigh phonological system (cf. Chaker, 2015). However, their equivalents are missing in LA biscripts, namely in RIL1 and RIL2 (cf. Galand, 1973). To examine the validity of this assumption, I meticulously analyze the data observed in the biscripts containing the vertical tribars, depending on epigraphic and philological comparisons.

The vertical tribars are found in three bilingual inscriptions in RIL. Fortunately, they are employed in names that are transcribed in Latin and Punic. In this section, I argue that the vertical tribar is a sibilant sound, likely /ʒ/, depending on a meticulous analysis of the data observed in those bilingual inscriptions and cross-dialectal comparisons in Pan-Amazigh. The following table emphasizes the names associated with the vertical tribars and their corresponding Punic and Latin equivalents.

| Tribaar III | RIL145 | RIL31 | RIL85 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Names |

L: COIVZANIS LA: G(H)•N |

P: BAAL-HANNONI LA: B-(H)N(H) |

L: [F]AVSTVS LA: FWST(H) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transcription | Z /z/ | H /h/ | S /s/ | Table 9: Bilingual Transcriptions of the Vertical Tribar in LA The vertical tribar ⵏⵏⵏ is used in RIL145 at the middle of the parental name (W-GH•N). The latter is transliterated in Latin as (COIVZANIS). If vowels are removed from the Latin word (COIVZANIS), the result is (CZN), which is a potential transliteration of (GH•N) (cf. Chabot, 1941, p. 38). It is possible that the Latin suffix (IS) is absent in GH•N because this name originates from Amazigh where such a morphological affix is unfamiliar. Therefore, it is clear that the Latin parental name (COIVZANIS) uses the sound /z/ to transcribe the vertical tribar ⵏⵏⵏ in RIL145. At least, this is the only bilingual example where there is a letter-by-letter transliteration of a parental name. The use of the Latin letter (C) /k/ instead of (G) might be due to pronunciation differences in both languages; this phenomenon is called phonological adaptation of foreign names in target languages. Phonological adaptation of foreign names is self-evident in any language because some sounds or clusters in source languages might be unfamiliar in target ones. A clear example of this phenomenon in LP inscriptions is the Punic transcription of the letter (P) to (F) in LA personal names (see RIL31: IEPDAT- IFDT, RIL2: ŠPṬ- ŠFṬ). Alternatively, the Latin (G) could also have been misrepresented as (C). Given the evidence from RIL145, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the vertical tribar ⵏⵏⵏ represents a sibilant, possibly a related variant like (z1). While RIL145 suggests a sibilant interpretation of the vertical tribar, likely (z1), RIL31 presents additional evidence from a bilingual LP inscription. The first Punic lines are decipherable according to Chabot’s translation (1941, p. 12).

It is clear that the Punic personal name (BAAL-HANNONI) corresponds to the LA personal name (B-HNH), and the Punic parental name (IEPDAT) corresponds to the LA parental name (YFDT). The translation of the Punic word (BAAL) is (B) in LA; both words might mean “the owner of.” The second parts of the personal names are (HANNONI) in Punic and (HANNO) in LA according to Chabot’s vocalization (1941, p. 12). In this personal name, the Punic sound (H) corresponds to the vertical tribar, that is, the vertical tribar represents the voiceless laryngeal /h/. The presence of the Punic letter (He) in RIL31 alongside other letters such as (Aleph, Nun, and Taw) suggests that this inscription belongs to the Later Punic script. This version differs from the one used in Dougga inscriptions (RIL1 and RIL2). I assume that the phonological adaptation of foreign names in LA or in Punic is the reason behind the Punic transcription of the vertical tribar as /h/. Therefore, the Punic letter (H) might be a phonological adaptation of the sound (z1) in LA. I believe that this argument is an appropriate explanation to the diverse Punic transcriptions given to the vertical tribar as well. Why does the Punic (H) correspond to the LA (Z1)? In fact, one of the phonological shifts that is observed in Pan-Amazigh is the change of the sound /z/ to /h/, /ʒ/, or /ʃ/ in Touareg, or the other way around (cf. Chaker, 2015, p. 9). Chaker (2015) states that the palatalization of /z/ would be almost a spontaneous palatalization because in the majority of cases there is no detectable contextual conditioning (azal, “day” > Touareg: ahǝl, ažǝl, ašǝl…) (Chaker, 2015, p. 9). The Zenaga dialect, which belongs to a different zone, also encounters this phonological shift. In Zenaga, the sounds /ʒ/ and /ʃ/ change to /z/ and /s/ in the plural form, for example: afouš “hand” ofessan “hands” amouj “will” mouzzen “wills” However, the sound /h/ is absent in the common Amazigh phonological system (Chaker, 2015). Therefore, I am skeptical about the use of this sound in the LA inscriptions. I argue that the (z1 ~ h) correspondence between LA and Punic in RIL31 is due to phonological adaptation of foreign names. RIL85 is a Libyco-Latin (LL) biscript where some names correlate with each other, L: [F]AVSTVS and LA: FWST(H). The personal name FAUSTUS is definitely of Latin origin because it is familiar in Latin literature, and it means “lucky, fortunate”. The Latin suffix (TVS) is transcribed as (TH) in the LA personal name FWST(H); the transliteration of the Latin suffix[6] in LA is also a good reason for its borrowing from Latin (cf. RIL252: CHINID-IAL/ KND-YL). Thus, the Latin letter (S) is transcribed as a vertical tribar in LA. Again, the vertical tribar is transcribed as a sibilant, likely pronounced in LA as /s1/ or /z1/. In comparison, the equivalent of the Latin name SACTUT is the LA name ZKTT in RIL151; the LA sign − /z/ corresponds to the Latin letter S /s/ in this inscription. This sound change is another instance where phonological adaptation occurs in foreign names. The table below demonstrates that phonological adaptations might be confusing; Latin LA Analogically, I argue that the vertical tribar is transcribed as /z1/ in RIL85 because of the phonological adaptation which occurred to the foreign name FAUSTUS / FWSTZ1. Therefore, the Latin sound /s/ might be realized as /z1/ in LA. Fournet (2014) argues that most Amazigh dialects do not have laryngeal, pharyngeal, and uvular phonemes in their core, authentically Amazigh vocabulary. He states that in Nigerian Touareg dialect, where the lexical influence of Arabic is weak, there are no laryngeal or pharyngeal phonemes in the phonological inventory. He adds that it should be also noted that the Ancient Tifinagh alphabets and the LP alphabet, used some two thousand years ago to denote what was certainly an Amazigh dialect, do not have the equivalents of the glottal stop /ʔ/, the voiceless pharyngeal /ḥ/, the voiced pharyngeal /ʕ/ (Fournet, 2014, p. 33). Perhaps, he does not mention the voiceless glottal /h/ because it could be represented by the tribars. In Tashelhit, the voiced laryngeal sound /h/ is produced with vocal fold vibration, and the geminate counterpart of this glottal fricative is not frequent in the lexicon (Ridouane, 2014, p. 210). This is a fact in the majority of Amazigh dialects, except in Touareg where this sound is frequent, bearing in mind that it corresponds with the sibilants /z/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/ in the rest of the dialects. Certainly, the vertical tribar might be either the sibilant /z1/ or the laryngeal sound /h/ in LA inscriptions. This assumption includes one problematic issue that is the presence of three variants of the sound /z/ in RIL inscriptions, (Z1, Z2, and Z3). Kossmann (2020, p. 877) makes a comparison between the phonetic values given to sibilants, namely the variants of (Z), in RIL inscriptions in the following table;

Table 10: The Variants of the Sound Z in RIL LP Inscriptions Certainly, the vertical tribar is a variant of the voiced sibilant /z/. Therefore, this sibilant might be the sound /z/, /ẓ/ or /ʒ/. Yet, a conditioned distribution pattern might explain the use of different variants for (Z) if it existed. In the following table, Kossmann (2020, p. 882) observes that the variants of (Z) are never used in the final position of words in RIL. Therefore, I assume that the vertical tribar might be a variant of (Z) that is mostly used in the final position.

Table 11: Distribution of the Variants of Z in RIL In fact, all these variants of (Z) are related to the laryngeal sound /h/ in Pan-Amazigh. This explains why it is transcribed as /h/ in RIL31. The following table provides some example of the well-attested /z/ ~ /h/ or /ʒ/ alternation in Pan-Amazigh (Haddadou, 2007).

Table 12: The /z/ ~ /h/ or /ʒ/ Alternation of Sibilants in Pan-Amazigh In Amazigh, the prefix (S-) indicating causality changes to /z/ when it coexists with the sounds /z/, /ḍ/, and /ẓ/. This phonological shift is called assimilation because the sound /s/ changes to become similar to the neighboring sound /z/, for example: azel “to run” - zuzel “to make run” (Touareg), azzel “to run” - ssizzel, zzizzel “to make run” (Ouargla), and azzel “to run” - zizzel “to make run” (Tamazight) (Haddadou, 2007, 957 ZL). Moreover, it might also change to (Ž) /ʒ/ or (Š) /ʃ/ when it occurs adjacently with the sound /ʒ/ in Zenaga, for example, eneh “to be inclined forward downward”- zeneh “to tilt forward downward, to cause incline downward” (Touareg) […] enji “to be sold”- jenj, ecenj “to sell” - enji, pl. enjan “sale” (Zenaga) (Haddadou, 2007, 604 NZ). Philologically, the parental name (W-ZWŽ-SN) includes three parts: (W-) meaning “son of”, the frequent suffix (-SN) meaning “their” (cf. MSNSN, MKWSN, NBDDSN, etc.), and the main root (Z-WŽ) bearing in mind that (Z-) is a prefix. Based on a lexical study, two roots might be related to (WŽ). Firstly, the derivatives of the root 890 WZ that share a common meaning of “a resilient plant” (thorny broom, wild asparagus, barely beard, etc.), that is, “their resilient person”. Secondly, the derivatives of the root 891 WZ that share the meaning of “tingling, shivering and numbing”, which could be a positive meaning in a personal name as well. The following table sums up the findings observed and analyzed in this section; this analysis is based on the study of three bilingual inscriptions; two of them associate the vertical tribar with sibilants /z/ and /s/ (RIL 145, 85). One of them assigns it the voiced laryngeal fricative /h/ (RIL31).

Table 13: Correspondences among the Vertical Tribar and Sibilants in LA In conclusion, these transcriptions are not accurate because they are not identical to each other. This diversity is due to the phonological adaptations that LA names encountered in Target languages, namely Latin and Punic (cf. RIL151: (LA) ZKTT- (L) SACTUT). Certainly, the vertical tribar cannot be the voiced sibilant /z/ or the emphatic /ẓ/ because these sounds have their own signs in LA. Yet, it should represent another sibilant, likely /ʒ/ due to its phonetic characteristics. The Punic (H) corresponds to the vertical tribar in RIL31, which might suggest that the tribar represents /h/. However, phonological evidence from Pan-Amazigh indicates a well-attested /z/ ~ /h/ alternation (or the other way around), particularly in some Touareg dialects (cf. Ridouane 2003). Given that the voiced laryngeal fricative /h/ is rare in native Amazigh vocabulary and often appears in Arabic borrowings, it is possible that the Punic transcription reflects a dialectal or phonological shift rather than a distinct phoneme. Therefore, the correspondence between Punic (H) and the vertical tribar does not necessarily contradict the hypothesis that the tribar originally represents a sibilant, likely /ʒ/. In addition, the potential root of the frequent name (W-ZWH-SN) is ZWH; the latter suggests that the prefix Z- might be the assimilated prefix S- indicating that the sound (H) is a sibilant as well, likely /ʒ/. The distinction between the vertical and horizontal tribars is based on data obtained from multiple biscripts. I observe that the horizontal tribar consistently appears in final positions and is absent in the roots of the potential words associated with this sign. Therefore, I assume that it may function as a final vowel. In contrast, I suggest that the vertical tribar might be a sibilant possibly a variant of /z/, likely /ʒ/. Its phonological correspondence with the laryngeal sound /h/ can be explained by the well-attested /z/ ~ /h/ alternation in Pan-Amazigh, particularly in certain Touareg dialects. 3- Discussion and Limitations We now understand why some researchers argue that the tribars might represent a laryngeal sound, while others suggest they might indicate vowel sounds (see Table 4). These conflicting phonetic values arise because scholars do not systematically distinguish between vertical and horizontal tribars. Moreover, those who propose a velar sound seem to be influenced by the modern phonetic value assigned to the tri-dot sign ⵗ in Tifinagh (cf. Sudlow, 2011, p. 33). In this section, I will tackle other important issues that support the distinctiveness of the tribar hypothesis, mainly the morphological and epigraphic features of the tribars and some of the limitations of those features. a- Feminine Prefix (T-) as Evidence for the Verbal Character of the Tribars The occurrence of certain Segment-Hs suggests these segments might have a specific grammatical or semantic function, potentially related to verbs or predicates. This hypothesis could be consolidated by the presence of the feminine marker (T) in some Segment-Hs, which provides strong evidence for their verbal character, indicating gender agreement with the deceased’s name. The verbal character of at least some Segment-Hs is indicated by their incorporation of a verbal feminine marker, specifically an initial T-. Evidence for this can be found in at least the following inscriptions: RIL (80, 104, 212, 276, 965, 968, and 969, 1125).

Table 14: Feminine Segment-Hs in RIL Inscriptions In these inscriptions, not only segment-Hs, which have the initial feminine marker (T) but also tribars, exhibit initial feminine markers (T). Both segment-Hs and tribars agree in gender with the personal name of the deceased, indicating that these segments function as verbal predicates. RIL 80 includes the common segment MSW in its feminine form, TMSW-TH; the personal name of the deceased might be BNT[?]. The puzzling BNS is recurrent but cannot be a personal name; Chabot (1941) assumes that it means “his tomb”. Additionally, in RIL 968, the recurrent segment appears to be appended with a feminine marker, (T). The isolated segment TYL, featured in the first line of this inscription and probably pronounced /tɑjlɑ/ might be a feminine personal name. RIL104, which is a BNS inscription as well, features the feminine personal name TBRN, and the second segment TBKNTH could be a Segment-H containing two verbs TBKN and TH indicating gender agreement. In RIL 965, the parental name of the deceased begins with WLT, which can only mean “the daughter of” in Pan-Amazigh. The second segment, TDMS[7], starts with (T), indicating a likely agreement marker. RIL 969 also contains a parental name starting with WLT, specifically WLT-MRT, and both the second and third lines, TRN-TH and TBRNG-H, respectively, begin with (T), again suggesting a feminine agreement marker. In contrast, RIL 211 and RIL 1082 provide evidence for an independent use of WLT, likely to link a personal name with a parental name: ZRTLN and MZKL in RIL 211, and MBTR WLT MGN[I] in RIL 1082. One potential argument against this interpretation of the independent WLT is the existence of at least one RIL inscription, namely RIL 222, where WLT is used independently in the leftmost line, the parental name, prefixed with a masculine (W-), is clearly in the rightmost line, and the non-onomastic segment in the middle does not feature any letter T that might be interpreted as a feminine marker. We acknowledge that this is strong evidence against this analysis. However, there is no principled reason to disregard the possibility that the two versions of WLT are homographs, with one meaning “the daughter of” and the other being a personal name. Moreover, WLT in (RIL211 and 1082) might be misrepresentations of the recurrent personal name YLT as well (RIL159, 220, 223, 225, 227). RIL216 is another challenging inscription because the two segments T[G]RN and [TH] feature initial markers T unless the deceased’s name is WMRT, and NMMN is a parental name lacking WLT (cf. HLT: RIL 1110, 1111; WHLT: RIL 161). However, if one assumes that these Segment-Hs are feminine nouns rather than verbs, the use of the initial (T-) and the final (-T) indicates that these words might be feminine titles (cf. Chaker, 1986). This assumption suggests that the tribars might be unknown suffixes that are coupled with titles in funerary LA contexts. Further research is needed to explain this important argument as well. To sum up, some inscriptions show that Segment-Hs might be verbs depending on their morphological features, namely the use of the initial feminine marker (T). Interestingly, some tribars also exhibit this morphological feature, that is, they are independent of Segment-Hs. Hence, Segment-Hs might be verbal collocations with certain funerary meanings and functions. The presence of the word WLT meaning “the daughter of” in some inscriptions supports this argument as well. Yet, this argument could be valid only if feminine Segment-Hs are not titles. b- Interchangeability vs. Distinctiveness The apparent interchangeability of the vertical and horizontal tribars, especially in Segment-Hs, presents challenges in assigning them distinct phonetic values. If we assume that the horizontal tribar represents an unknown suffix or a final vowel while the vertical tribar corresponds to a variant of (Z), likely (Ž), inconsistencies arise in the interpretation of these segments. The following table demonstrates the potential interchangeable use of the horizontal and vertical tribars in Segment-Hs. For instance, the recurrent Segment-Hs MSKRH and MSWH exhibit both tribars interchangeably; I use the letter (I) to represent the horizontal tribar only for a descriptive reason.

Table 15: MSKRH and MSWH’s Occurrences in RIL Apparent interchangeability explains why many scholars regard both tribars as variants of the same phoneme rather than distinct sounds. Yet, the distribution of the tribars in Segment-Hs also demonstrates that these tribars are not part of the roots of the Segment-Hs because these segments sometimes occur without any tribars, for example MSKR and MSW. Additional evidence supporting the apparent interchangeability of the tribars includes: - Both tribars coexisting with different Segment-Hs; for example both of them are found in MSKR and MSW (i.e. RIL 144, 158, 185, 182, 324, 326, 724). Apparent interchangeability, therefore, is a counterargument against the previous findings analyzed in earlier sections, namely; the horizontal tribar might be an unknown suffix or a final vowel, and the vertical tribar might be a variant of (Z), likely (Ž). c- Tribar Clusters as Evidence for the Tribars’ Distinctiveness However, this apparent interchangeability might be conditioned by certain comparative linguistic and epigraphic patterns. On the first hand, the vertical and horizontal tribars co-occur in different lines of the same inscription, which suggests that they might have different phonetic values. Yet, I acknowledge that some graphemes like ⵎ (open to the right), its variant ⵎ (open to the left) are employed interchangeably to represent the sound /d/ in RIL inscriptions. For example, the variants of this grapheme are found in MNKD as follows;

Table 16: The Variants of the Grapheme D in MNKD This observation suggests that co-occurrence of variants of the same graphemes is well attested in RIL inscriptions, and it might not be enough to distinguish between different graphemes depending on co-occurrence technique. Analogically, I argue that co-occurrence is not a good argument for the tribar distinctiveness hypothesis. On the other hand, both tribars cluster if they co-exist one next to the other at the end of Segment-Hs or names; particularly, the horizontal tribar tails the vertical one. The table below exhibits some examples of clustered tribars;

Table 17: Clustered Tribars in RIL Inscriptions There are at least 17 examples of clustered tribars in RIL inscriptions. These clustered tribars may be categorized into four types: Vertical + Horizontal (VH), Horizontal + Vertical (HV), Vertical + Vertical (VV), and Horizontal + Horizontal (HH). While the common cluster (VH) is found in 13 RIL inscriptions, the other clusters (HV, HH, and VV) are employed only once in RIL inscriptions. The prevalence of the cluster (VH) suggests that the distribution of the tribars might be conditioned by a certain linguistic pattern or writing convention because the systematicity of the (VH) cluster cannot be a random occurrence. Therefore, I assume that these clusters, mainly (VH and HV), could be good arguments for the distinctiveness tribar hypothesis because employing two different clustered graphemes might be a good reason for their distinct phonetic values. Previously, I have argued that the initial feminine marker (T-) is used with some tribars[8] as a morphological prefix featuring the verbal character of the tribars. Comparatively, the common cluster (VH) also suggests that the clustered tribars might be different verbs, that is, two clauses. To sum up, the tribars are different from the variants of the grapheme (D) because they are clustered one next to the other, namely the prevalent cluster (VH). Therefore, the tribars might be different graphemes used in hundreds of RIL inscriptions. Conclusion In conclusion, the horizontal tribar in RIL inscriptions, lacking Punic or Latin transliterations, consistently appears in final positions, both in non-onomastic (RIL1, RIL2, RIL451) and onomastic contexts (RIL72). Philological analysis of the non-onomastic words indicates it likely represents either an unknown suffix or a final vowel. Conversely, the vertical tribar, present in both LL and LP bilingual inscriptions, might be a variant of /z/, likely /ʒ/. Its correspondence with Punic (H) and Latin (S) might be attributed to the phonological adaptation of foreign names and explained by a common phonological shift in Pan-Amazigh, namely the /z/ ~ /h/ alternation. The distinction between these tribars is further supported by their clustered occurrences, particularly the prevalent VH, and the presence of the initial feminine marker T-, indicating potential verbal functions. Despite phonetic inconsistencies due to apparent interchangeability of the tribars, the weight of evidence, including biscript and Pan-Amazigh analysis and distribution patterns, supports the distinctiveness of these tribars. The tribars used in Segment-Hs, therefore, are likely recurrent verbs or suffixes within the RIL inscriptions. The analysis of these tribars sheds light on the morphology and syntax of the Libyco-Amazigh language, providing valuable insights into the funerary practices and LA writing conventions of the Amazigh people.

References Boukous, A. 2009. Phonologie de l'Amazighe. Rabat: Publications of IRCAM. Camps, G. 1993. “A la recherche des Misiciri: cartographie et inscriptions libyques.” à la croisée des études libyco-berbères : mélanges offerts à Paulette Galand-Pernet et Lionel Galand. Drouin J., Roth A. ed. Geuthner: 113-126 Chabot, J. B. 1941. Recueil des inscriptions libyques. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. Chaker, S. 1986. “A propos de la terminologie libyque des titres et fonctions.” Annali del’Istituto Universitario Orientale: 541-562. ____________. 1996 a. “Manuel de linguistique berbère II, syntaxe et diachronie.” Algeria: ENAG. ____________. 2015. “Phonologie et Phonétique.” Encyclopédie Berbère 33. doi: hal-01780808 Cid Kaoui, S. 1907. Dictionnaire français-Tachelh't et Tamazir't (dialectes berbères du Maroc). Paris: Ernest Leroux. Dallet, J. M. 1982. Dictionnaire Kabyle français, parler des Al Mangellat, Algérie. Paris : Société d'études linguistiques et anthropologiques de France. Faidherbe, L. G. 1877. Le zenaga des tribus sénégalaises. Paris: Ernest Leroux. Février, J. 1956. “Que savons-nous du libyque ?” Revue africaine : 263-273. Fournet, A. 2014. “Les consonnes du chamito-sémitique et le proto-phonème *H du berbère.” P. d. Proche-Orient, ed. Bulletin d’études orientales : 23-50. doi:10.4000/beo.1257 Galand, L. 1973. “L'alphabet libyque de Dougga.” L'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée 13-14 : 361-368. Haddadou, A. M. 2007. Dictionnaire des Racines Berbères Communes. Algeria: Haut Commissariat à l’Amazighité. Justinard, C. 1914. Manuel berbère marocain (dialecte Chleuh). E. Guilmoto, ed. Librairie orientale et Américaine. Kossmann, M. G. 2020. “Sibilants in Libyco-Berber.” The American Oriental Society 140 : 875-888. doi: 10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.4.0875 Krahmalkov, C. R. 2001. “A Phoenician Punic Grammar.” Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. Motylinski, A. d. 1898. Le djebel nefousa. Paris: Ernest Leroux. Pichler, W. 2007. Origin and Development of the Libyco-Berber Script. Cologne: Rudiger Koppe Verlag. Ridouane, R. 2014. “Tashlhiyt Berber.” Journal of the International Phonetic Association. doi:10.1017/S0025100313000388 Rössler, O. 1958. “Die Sprache Numidiens.” Sybaris. Festschrift H. Krahe : 94-120. Wiesbaden. Sfaxi, I. 2014. “L'onomastique libyque : son intérêt - état des recherches.” Revue des Etudes Berbères (REB) (9) : 565-575. ____________. 2022. “La Valeur Sémantiques du Libyque YSK et ses Variantes.” Études et Documents Berbères: 105-112. Sudlow, D. 2011. “The Tamasheq of North-East Burkina Faso. 2nd ed.” Cologne: Rudiger Koppe Verlag. Vaan, M. d. 2008. Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the Other Italic Languages (Vol. 7). A. Lubotsky, ed. Leiden: Brill. [1] Recueil des inscriptions libyques (RIL). [2] Some researchers argue that some Segment-Hs could be ethnonyms, that is, tribal names (Camps, 1993; Chabot, 1941; Sfaxi, 2014). Yet the ethnonym interpretations do not provide any explanations to the significance of the tribars (H). However, my concern in this article is not to explain the meaning of Segment-Hs but to determine the phonetic value of the tribars in RIL. [3] Mater lectionis is a Latin word meaning a consonant letter used to indicate a vowel sound. [4] See (H) in Appendice, table des noms propres. I could not find these inscriptions (RIL737, 798, 807) in the available online version of RIL (Chabot, 1941). [5] Author’s translation from French. [6] The Latin suffix (US) is kept in one Latin loanword in Tashelhit and Moroccan darija; (afulus) or (fellus) meaning “chick, chicken” comes from (pullus) “foal, chick, young of an animal” (cf. Vaan, 2008, p. 502). [7] Chabot (1941) comments that this segment could be either DMS or RMS (see RIL965). [8] See (RIL 80, 104, 965, 968, 969, 216). DOWNLOAD ISSUE Volume 4 • Issue 1 • Fall 2025 INSTITUTION |