Standardization of Tifinagh Writing and its Adequacy

Peer-Reviewed Article

AUTHORS: Abderazaq Ichou and Said Fathi

Standardization of Tifinagh Writing System and its Adequacy

Abderazaq Ichou and Said Fathi

Hassan II University

Abstract

Developing a writing system specific to the Amazigh language is undoubtedly a significant step in its revitalization. This initiative has contributed to the creation of a distinct writing script for Standard Tamazight, differentiating it from other languages. Moreover, it has helped preserve the Tifinagh script from falling into disuse and breathed new life into it. The purpose of this paper is to explore the standardization of the Tifinagh Alphabet, specifically examining the approach adopted by Tamazight language planners and evaluating the adequacy of the Tifinagh writing system based on Cooper's framework.[1]

Key words: Tifinagh, language standardization, script, adequacy

Introduction

Graphization can be considered a crucial initial step in the language standardization process. Writing systems are essential because they enable a language to transition from an oral to a written form, thereby facilitating the development of literacy materials and contributing to the reduction of linguistic variation within a community.[2] Haugen emphasizes the importance of a writing system in language standardization, stating that "it is a significant and probably crucial requirement for a standard language that it would be written."[3]

Similar to many other languages, historical records indicate that the Amazigh language writing system is not a recent tradition, but rather dates back many centuries prior to its revitalization in the late 20th century. According to Boukous, it is widely documented that Amazigh-speaking communities utilized various writing systems, including the Libyco-Berber or Tifinagh script. This script was used alongside other writing systems borrowed from communities with which the Amazigh people had contact. Consequently, a substantial body of Amazigh written heritage exists, comprising "corpora of ancient inscriptions in Libyan-Berber," "a set of inscriptions in Tifinagh," "pieces of Amazigh Islamic literature written in Arabic characters," and "a set of texts, glossaries, and grammars in Latin characters."[4] Furthermore, within the context of Amazigh language revitalization, Boukous reports that the 1960s saw the emergence of writings in neo-Tifinagh.[5]

The preceding overview of the various writing systems used by Amazighophone communities indicates that the desire to develop a specific writing system for the Amazigh language is not a recent phenomenon. These attempts, as evident from the existing materials, lack unity due to their association with different periods in the history of the Amazigh language and its people.[6] Although these efforts provide a foundation for the development of a writing system, the true transition of the Amazigh language, particularly in Morocco, from an oral to a written language effectively commenced with the adoption and codification of the Tifinagh alphabet by the Royal Institute for Amazigh Culture (IRCAM) in 2003. The use of Tifinagh in teaching, learning, and compiling Amazigh neo-literature exemplifies the development of the Amazigh language as a written language. In the following sections, we will focus on the standardization process of the Tifinagh script in Morocco, examining the pre-standardization steps, the adopted approach, and the characteristics of the standardized product. We will also evaluate the adequacy of the Tifinagh script as a writing system based on Cooper's criteria for assessing writing systems.[7]

Standardization of Tifinagh Alphabet

Boukous argues that the first step to be taken to develop a standard Tifinagh alphabet is to conduct a thorough survey of all the variants of Tifinagh that have been used or are still in use within the Amazigh domain. According to him, this study contributed to identifying three major variants of the Tifinagh alphabet: Proto-Tifinagh or Libyco-Berber, current Tuareg Tifinagh, and Neo-Tifinagh.[8]

First, Proto-Tifinagh consists of Eastern, Western, and Saharan variants. According to Ameur et al., deciphering 23 signs of the Eastern variant was made possible thanks to the Punic-Libyan bilingual inscriptions of Dougga. The Saharan variant has the advantage of presenting continuity in time up to the current Tuareg variants, which has relatively facilitated the deciphering of its signs. Conversely, the Western variant still resists decipherment.[9] Table 1 below compares the equivalence of some letters in the three variants of the Proto-Tifinagh alphabet:

Table 1: some letters equivalence in Proto-Tifinagh variants[10]

The three variants of Proto-Tifinagh share some basic characteristics:

a. They are basically consonantal writing systems;

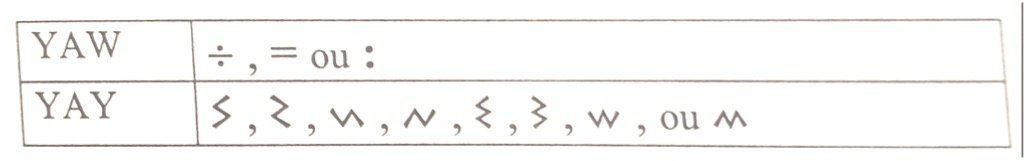

b. Vowels appear only in word final position. However, some semi-vowels “YAW” and “YAY” appear with assistance of some letters (cf. Table 2);

c. None of these variants is cursive;

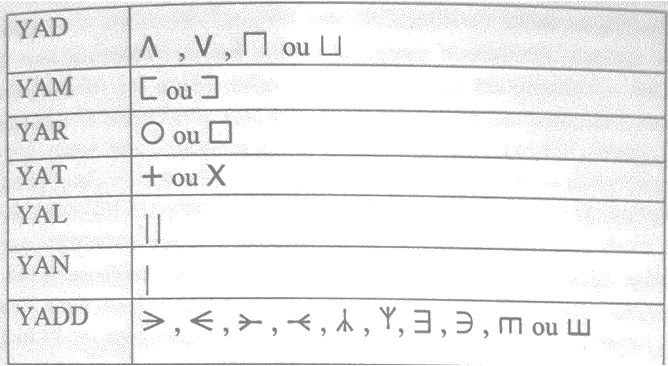

d. Some letters are similar in form (cf. Table 3)

Table 2[11] :

Table 3[12]:

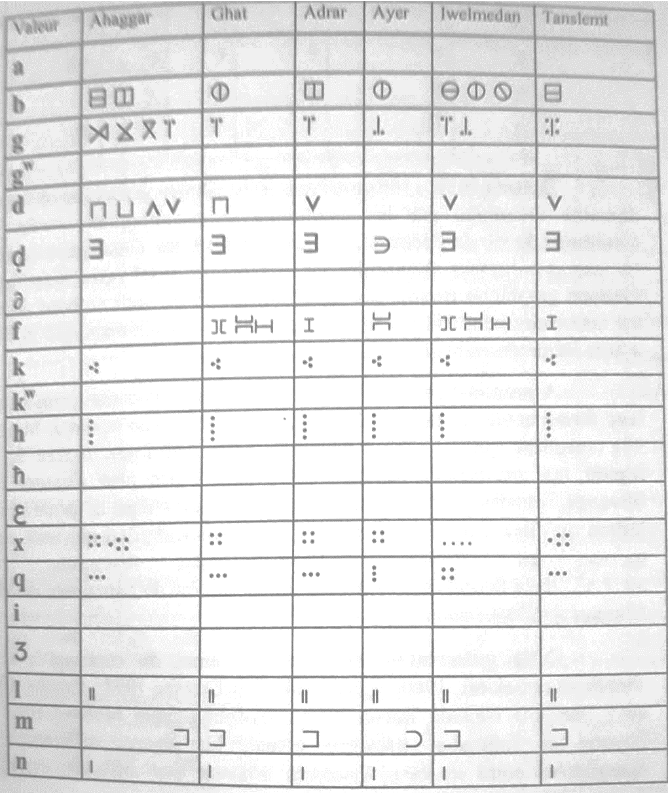

Second, Tuareg Tifinagh is composed of six variants: Ahaggar, Ghat, Adrar, Ayer, Iwelmedan, and Tanslemt. The writing system is marked by a profound unity. The vowels do not exist in this writing system. All the letters are consonants and semi-consonants. Moreover, the majority of letters have a similar shape. Table 4 gives a clear example of these variants:

Table 4: Current Tuareg Tifinagh Variants[13]

According to Ameur et al, these variants are currently used by the Tuareg people, who are the only Amazigh people to have preserved writing in this ancient script. One in three men and one in two women can write it without difficulty. Recently, the Tifinagh alphabet has been used as a pedagogical tool within the framework of the campaign against illiteracy.[14]

Ameur et al reveal that Tuareg Tifinagh consists of various regional variants, which results in some divergences at the level of the shape of some signs (letters) corresponding to Tuareg dialectical variations. Sometimes, even from one region to another, the number and form of signs can change. However, the texts are generally still intelligible.[15]

In addition, Ameur et al note that, similar to ancient Saharan Tifinagh, Tuareg Tifinagh involves the sign “.,” which is used to denote word-final vowels that are called tighratin (masc. tighrit). For the Ahaggar, Ghat, and Adrar Tifinagh variants, this sign is employed only for the vowel “YA” /ⵢ/ when it appears in a word-final context. The vowels “YI” and “YU” are represented by the semi-vowels “YAY” and “YAW” when they appear in the word-final position.[16]

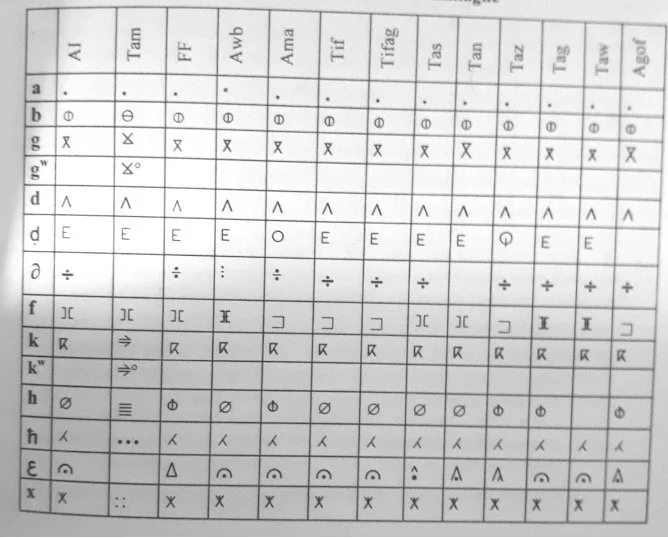

Third, Neo-Tifinagh specifically involves the variants of Tifinagh developed in the 1960s by the Berber Academy (L'Académie Berbère) based on Tuareg variants. It is largely adopted in Morocco and Algeria (Kabyle). Neo-Tifinagh also involves different variants, which are either newly developed or have resulted from editing the imperfections of the variant proposed by the Berber Academy (Agraw Imazighen, AI). These variants include Tamazgha (Tam), Fus deg wfus (FF), Arabia Ware Benelux (Awb), Amazigh (Ama), Tasafut (Tas), Tamunt (Tan), Tamazight (Taz), Tamagit (Tag), Tawiza (Taw), and Agadir O’flla (Agof). Table 5 below presents some examples of these variants:

Table 5: Variants of neo-Tifinagh[17]

The unity of these variants is more evident than that of the other two. They include consonants, semi-consonants, and vowels. Their letters are mostly borrowed from Proto-Tifinagh and the Tuareg alphabet. In addition, the forms of some letters are changed, and some letters are added, specifically those referring to affricates, emphatics, and labio-velarization.[18]

Having characterized the variants of the Tifinagh alphabet, the next step is to discuss the approach adopted in standardizing the spelling of Amazigh. It is worth noting that standardizing Amazigh spelling is not an easy task. The variety that characterizes the notations of the Amazigh alphabet implies that the adopted approach should be combinative, including all the variants. In addition, the implementation of the standard alphabet and its acceptance by the people should be taken into consideration.

The Approach

Boukous contends that the approach employed to standardize Amazigh script involves five main stages:

The establishment of a database comprising the different variants of Tifinagh on the basis of a broad survey of the literature in order to identify the magnitude of variation in the notations used;

The capitalization of the results of the analysis of the sound system of the main dialects of Morocco in order to decide on a common phonological system comprising a finite number of distinctive units; and

The development of a unified Tifinagh graphic system on the basis of the notations currently in use according to the following principles:

a. Historicity: the oldest graphemes are preferred to the most recent ones;

b. Univocity: to each grapheme corresponds one sound;

c. Simplicity: the graphemes whose configuration is simple are preferred to those whose form comprises more than one element;

d. Coherence: the graphemes which render different sounds are eliminated; and

e. Economy: the preferred graphemes are those satisfying the gain/cost ratio in terms of technical designing and pedagogical efficiency.

The piloting of the product thus evaluated internally was conducted among a sample made up of researchers at the IRCAM, namely educationalists, litterateurs, as well as among experts in the field of Amazigh studies outside the IRCAM, nationals and internationals, associative, actors, creators, and so on; and

The establishment of the normalized spelling in education is facilitated through textbooks, multimedia, extracurricular tools and children’s literature books, and also in the production of neo-literature.[19]

The measures above show very interesting facts about the approach adopted to standardize the Tifinagh alphabet. First, it is based on a variationist approach. Its objective is to include all the variants of Tifinagh. The creation of the standard form is dependent on all the other variants. Hence, the sounds comprising the standard form are representative of all the other variants. The standard form neither favors one variant over the others nor degrades it. Boukous explains that:

The approach adopted in the preparation of standard Tifinagh alphabet satisfies the needs required by the planning of this alphabet in order to adapt it to the phonological system of Moroccan Amazigh. That is why it was necessary to make amendments, which have changed the form of some signs borrowed from the notation of neo-Tifinagh.[20]

This statement demonstrates that the new standard Tifinagh is a combination of the borrowings from the Neo-Tifinagh writing system and a set of changes and additions dictated by the requirement to make the new standard Tifinagh correspond to the needs of the phonological system of Moroccan Amazigh. Boukous points out that the standard Tifinagh IRCAM system is composed of the majority of the letters of neo-Tifinagh. While vowels, semi-vowels and some consonants are kept without any amendments, for other consonants, either they are changed or a diacritic sign (w) is added to them. Therefore, the changes are represented in the following way:

1. Labio-velarized consonants are added to the consonantal system to respond to the phonological requirements of Standard Moroccan Tamazight. To represent them, a diacritic (w) is attached to the primary consonant. Hence, we find: kw and gw for kw and gw. Examples are amddakwkwl (amddakwkwl) “friend” and tadgwgwat (tadgwgwat) “evening”;

2. The emphatic consonants ṭ, ḍ, and ṣ are represented by neo-Tifinagh signs ⵟ, ⴹ, and ⵚ. However, ẓ and ṛ are noted by ⵥ and ⵕ instead of neo-Tifinagh signs to guarantee simplicity. Examples are ⴰⵟⵟⴰⵏ aṭṭan “illness”, ⴰⴹⴰⵕ aḍaṛ “foot”, ⵚⴽⵓ ṣku “build”, ⴰⵥⵓⵕ aẓur “root”, ⴰⵕⴰ aṛa “give!”

3. the sounds representing f, l, ε, and h are modified as follows:

a. Adding a ligature: f is represented by the symbol f in place of ][; I is used to note the lateral I in order to separate it from the geminate n (nn), for instance ⴰⴼⵓⵙ afus “hand” and ⵉⵍⵍⵓⵍⴰ illula “it clotted”.

b. The pharyngeal ε is rendered by the sign ⵄ. This sound exists neither in traditional Tifinagh nor in current Tuareg, but it is found in the sound system of Standard Moroccan Tamazight .

c. The laryngeal h appears in traditional variants as ⵀ or ⴱ; in standard Tifinagh, it is rendered in h “ⵀ” to distinguish it from bilabial b “ⴱ”. Examples are ⵓⵀⵓ uhu “no” and ⵉⴱⵉⵡ ibiw “bean.”[21]

1.1 The adequacy of the Tifinagh Alphabet

The fact that the approach adopted to prepare the standard Tifinagh is based on clear principles lends support to the adequacy of standard Tifinagh as a writing system. The core principles of the approach appear to go hand in hand with the criteria for the adequacy of writing systems set by different scholars.[22] In the following, before we discuss the adequacy of the Tifinagh alphabet, we will first shed light on the Arabic script. We will reveal the main arguments provided by its proponents and examine its strengths and weaknesses.

a. Arabic script

The choice of the Arabic script for writing the Amazigh language is basically grounded in four main arguments. First, some proponents of the Arabic script argue that its adoption facilitates the learning of the Amazigh language and its transmission to other languages. In addition, they believe that the Arabic script is easy to learn and is widespread among Amazighophones. Second, other supporters of the Arabic script contend that its use ensures historical continuity, arguing that the Arabic script has been employed for writing the Amazigh language, particularly in writing religious texts. Hence, its use will contribute to preserving the written heritage. Third, for others, the adoption of the Arabic script can facilitate communication between Amazighophones and Arabophones, which will contribute to unifying efforts to serve the Amazigh language and culture. Fourth, other advocates of the Arabic script insist on its use given its status as an aspect of the cultural identity of the region. Therefore, its employment enhances this cultural aspect.[23]

These arguments seem legitimate and support the choice of the Arabic script as a strong alternative for writing the Amazigh language. However, it is highly contested in the public debate surrounding the question of which script is suitable and practical for writing the Amazigh language, especially in the post-officialization period. Different scholars and journalists have criticized the use of the Arabic script as an option to write the Amazigh language[24] (see also Skounti[25]). The first remark made against the Arabic script is that its proponents are mainly politicians. Their support for the Arabic script is motivated by political and ideological considerations rather than scientific ones. Belqacem reveals that the ultimate objective of advocates of the Arabic script is to subjugate the Amazigh language. The supporters of the Arabic script are mainly Islamists and Arab nationalists (PJD members, as an example). These activists' attitudes are paradoxical. Until recently, they strongly opposed the officialization of the Amazigh language, considering it only a set of undeveloped dialects, and even after its standardization, they considered the standardized form an artificial language prepared in the IRCAM laboratory. In addition, they argued that Tamazight defenders held separatist goals and served the interests of Zionist and Francophone ideologies. However, the recognized change in the status of the Amazigh language, its officialization, and standardization have pushed the proponents of the Arabic script to change their attitudes toward the language and alter their discourse from total rejection to adoption of a new discourse, calling for its integration into public life and considering it part of their political agendas. Therefore, their insistence on adopting the Arabic script for writing the Amazigh language is meant to shape the Amazigh language's future in a way that does not disrupt their political orientations and programs and does not cause any harm to the status quo.[26]

Falling in the same line of reasoning, El Guabli argues that the battle over which script or alphabet is suitable to write Tamazight should not decoupled from its correlation with the battle over Morocco’s Amazigh identity and the easy way to discard or reclaim it. He stresses that the ultimate objective of supporters of adopting Arabic script to write Tamazight is “to contain Imazighen within the fold of their Arab-Islamic world view of Morocco as an Arab-Muslim country.[27]

In addition to the above external factors, the rejection of the Arabic script is attributed to some of its internal characteristics, which make it inadequate to respond to the phonological and orthographic aspects of the Amazigh language. First, the Arabic script does not involve an equivalent letter or sound for the short vowel “E” “ⴻ”. This is due to the absence of this short vowel in the Arabic language. This short vowel has utmost importance in the phonetic and orthographic system of the Amazigh language.[28] The comparison of the words below in terms of their writing in the Arabic script, Latin script, and Tifinagh explains this point:

Arabic Form Latin Form Tifinagh Form Meaning of the Word

أگـلا Agla ⴰⴳⵍⴰ Wealth/Properties

أگـلاّ Agella ⴰⴳⴻⵍⵍⴰ Honesty

ئگـنا Igna ⵉⴳⵏⴰ To stitch the cloth

ئگـنّا Igenna ⵉⴳⴻⵏⵏⴰ The sky

The examples[29] above show that the absence of an equivalence for the short vowel “E” “ⴻ” in Arabic causes significant similarity in writing and pronunciation, leading to serious confusion in meaning between many Amazigh words when written in Arabic script without diacritical marks. However, writing these words in Tifinagh or Latin scripts eliminates this confusion. The Arabic script offers a partial solution to this orthographic problem; the absence of “E” “ⴻ” is compensated for by adding a "sukun" (zero-vowel) or a "shadda" (consonant doubling) mark above the Arabic letter that follows the sound “E” “ⴻ”. However, the Arabic "sukun" mark does not accurately represent the actual Amazigh pronunciation except in some cases.

Second, when writing in the Arabic script, Amazigh language requires the use of at least four Arabic diacritical marks, namely “shadda” (consonant doubling), “sukun” (zero-vowel), “ḍamma” (mark for “o” or “u”), and “kasra” (mark for “e” or “I”), and this applies to tens of thousands of words in Tamazight. Sometimes, it is necessary to use “shadda” and “ḍamma” together above the same letter. In the absence of Arabic diacritical marks, the likelihood of mispronouncing those Amazigh words increases or pronouncing them in a way that confuses them with other words that have completely different meanings is highly plausible. It is well-known that the incorrect pronunciation of Amazigh words often leads to severe distortion of meaning, whether it concerns verbs or nouns.

Belqaçem reveals that Arabic diacritical marks are impractical (due to their small size, difficulty in reading, and ease of omission) and are often abandoned by Arabic writers, who expect the reader to make an extra effort to estimate the pronunciation with an acceptable margin of variation that does not harm the meaning. However, this approach is not feasible in Tamazight, which relies on precise pronunciation to determine meaning and distinguish between different words that share a common or similar root. The underlying reason for the necessity of using diacritical marks (when writing Tamazight in Arabic script) is primarily due to the absence of a letter equivalent to “E” in the Arabic alphabet, and secondly due to the Arabic orthographic convention of using the shadda (double consonant) mark instead of repeating the letter. The following Amazigh words are clear examples of this situation. Let us compare the writing of the words in Arabic script, Latin script, and Tifinagh script:[30]

Arabic Form Latin Form Tifinagh Form Meaning of the Word

أكال Akal ⴰⴽⴰⵍ Land

أكّال Akkal ⴰⴽⴽⴰⵍ loss/ Defeat

تادارت Tadart ⵜⴰⴷⴰⵔⵜ Wild Meant

تادّارت Taddart ⵜⴰⴷⴷⴰⵔⵜ House/Home

Third, the Arabic alphabet does not distinguish between the vowels “I” and “u” and the semivowels “y” and “w”. The Arabic alphabet represents these four sounds using only the letters "و" and "ي" (“waw” and “ya”). Therefore, it is necessary to use diacritical marks in the middle or at the end of Amazigh words written in the Arabic script. The reason for this limitation is that the Arabic language does not require this orthographic distinction between the sounds "i" and "y", on the one hand, and the sounds "u" and "w", on the other hand, whereas Tamazight relies heavily on this distinction. The following words support this claim. The examples compare the Arabic, Latin, and Tifinagh scripts:[31]

Arabic Form Latin Form Tifinagh Form Meaning of the Word

أرِي Ari ⴰⵔⵉ To write/He writes

أري Arey ⴰⵔⴻⵢ To protect / He protects

أمسُّوي amessuy ⴰⵎⴻⵙⵙⵓⵢ Carpet

أمسْوي ameswi ⴰⵎⴻⵙⵙⵡⵉ Drink

b. Tifinagh Script

Cooper suggests that the adequacy of writing systems can be judged based on two major criteria: a) psycholinguistic or technical, and b) sociolinguistic.[32]

On one hand, psycholinguistic criteria involve evaluating how easy it is to learn, read, write, and reproduce a script, as well as its adaptability to other languages and modern printing techniques. According to Cooper, citing Berry[33], these criteria can be conflicting, where something easy to read may not be easy to write or print, and something easy to learn may not be easy to use.[34]

On the other hand, sociolinguistic criteria play a more crucial role in determining whether a script is accepted or rejected. Cooper highlights that social factors, such as religious affiliation, have historically influenced script choice. For example, European Jews used Hebrew to write Judezmo and Yiddish, not because of its technical superiority, but due to religious reasons. Similarly, non-Arab Muslims used Arabic, Roman Catholic Slavs used Latin, and Orthodox Slavs used Cyrillic, all driven by social rather than technical considerations. Cooper argues that the strongest evidence for the importance of social factors is when different groups use different scripts for the same language. For instance, Serbo-Croatian is written in Latin script by Catholic Croats, Cyrillic script by Orthodox Serbs, and was previously written in Arabic script by Bosnian Muslims.[35]

Concerning the psycholinguistic criteria, the measures involved in the approach give clear signs that the standard Tifinagh alphabet meets different standards. The system is very distinguishable in terms of the principle of “univocity”, in which each grapheme stands for one sound. This principle, in fact, facilitates the learning, reading, and writing of Tifinagh. The issue of the gap between speech and writing that characterizes many writing systems of many languages is almost neutralized in the case of the Tifinagh Alphabet; all sounds have their corresponding letters. In addition, unlike other writing systems, Tifinagh letters appear in regular forms and their shapes do not change according to their position in the word, as in Arabic. Furthermore, the standard Tifinagh alphabet is very distinguishable in terms of the direction of reading-writing. Historically, it has been noted that the system allows various directions: left-right, right-left, top-down, and bottom-up. It is very special in this regard. Yet, the direction adopted in writing standard Tifinagh is the left-right one.[36]

Another technical criterion that promotes the adequacy of Tifinagh as a writing system is its coding. According to Boukous, the fact that the writing system received international approval under the name “Unicode Tifinagh-IRCAM” represents a great achievement for the whole language. This is because it allows Amazigh language to benefit from new information and communication technologies. It also enables the language to enter “the era of internationalization of processing and exchanging information and electronic publishing, while abiding by the standard necessity for coding, like other spelling systems around the world.” [37]

As far as the sociolinguistic criteria are concerned, we assume that the rejection or acceptance of Tifinagh script and the public debate it has generated recently are based on political and ideological rather than social or functional considerations. Its adoption in Morocco was in 2003. The decision was taken immediately after the integration of Amazigh into the educational system in the same year. Tifinagh was selected by King Mohammed VI as the suitable script for writing Amazigh after gaining 14 votes in the elections conducted in IRCAM about which script should be used to write Amazigh. The results of the elections imply that there was strong competition between the Tifinagh script and the Latin script, which received thirteen votes, while the Arabic script seemed to be out of the race, as it received only five votes. Yet, within the same year, mainly on February 10th, 2003, Tifinagh received official recognition from the Moroccan king Mohammed VI as the script to be employed in writing Amazigh. Its adoption at school was immediate after its recognition because it was in the same year, 2003, that the Amazigh language was integrated into 317 Moroccan primary schools. Starting from this point, IRCAM invested a lot of effort in both the standardization and implementation of the Tifinagh script. Thus, the status of Tifinagh and the whole debate associated with it recently are shaped by ideological and political considerations. Both the arguments presented against it and the timing in which the debate was fueled add more legitimacy to the strong position of Tifinagh.

First, the timing in which the discussion about the usefulness of the Tifinagh script was reopened is questionable because the script has already made considerable advances in a number of sectors. Over a period of more than ten years, a plethora of books, translated works, stories, novels, and textbooks have been compiled using the Standard Tifinagh script. It is also widely used in primary schools, universities, and training centers. In addition, after its coding, it has been integrated into digital technology, and people have become able to use it in their daily internet activities. Therefore, evaluating it after a long period of time and after significant efforts have been invested to make it comply with international standards seems more aimed at blocking the enactment of the official character of the language rather than assessing whether Tifinagh is the right script to use for writing the Amazigh language. It is worth noting that the debate about the Tifinagh script was reinitiated during the period between 2011, when Amazigh was officially recognized, and 2019, when the organic law 26/16 was issued. So, during this period, instead of focusing on enacting the official character of Amazigh, the script debate was reopened, potentially to slow down the enactment process. This is actually what happened, as the issuance of the organic law took almost eight years.

Second, the arguments provided by the opponents of the Tifinagh script can be characterized as being based on political and ideological stances rather than scientific assessments of the script's utility. Supporters of alternative scripts, namely Arabic and Latin, argue that Tifinagh is unsuitable due to several weaknesses. Firstly, it allegedly hinders the widespread adoption and dissemination of the Amazigh language. Secondly, it does not facilitate the teaching and learning of Amazigh. Thirdly, Tifinagh is not of Amazigh origin.[38] Therefore, they advocate for either adopting a national script more familiar to the public, to bridge the gap between the public and the Amazigh language, or a Latin script, given its universality.

The assumptions presented above were refuted by counter-arguments provided by scholars who support the Tifinagh script. Assid, for example, lists several characteristics that make the Tifinagh script a suitable choice for writing the Amazigh language. Firstly, its use in schools over the years has shown that children learn it easily compared to other scripts. Secondly, it is the only script that includes all the sounds of Amazigh, facilitating accurate and faithful writing. In contrast, the Arabic script lacks equivalent letters for some Amazigh sounds. Thirdly, Tifinagh involves vowels similar to the Latin script, which is essential for reading texts. Adopting the Arabic script, on the other hand, would require the vocalization of Amazigh texts and words to ensure easy reading. Fourthly, all Tifinagh letters are independent, unlike Arabic, where the form of a letter changes according to its position in the sentence.[39] Erraji has explained why controversy has surrounded Tifinagh since its adoption in 2003, despite its practical features. He notes that public debates about Amazigh are often driven by political and ideological agendas, with seminars and conferences typically involving political and civil participants with ideological views, while experts are rarely involved.[40]

In the same vein, Skounti, while analyzing some fragments of the PJD’s secretary general speech, Abdelilah Benkiran, in which the latter attacked Tifinagh script and described it as “Chinese script”, points out that a number of researchers, such as Malika Hashid, Salem Chaker, and Suleiman Hashi in Algeria, and Ahmed Skounti, El Mostafa Nami, and Abdelkhalek Lamjidi in Morocco, proved that Tifinagh is closely related to the rock art engraved and dyed on the stone and in the caves. It is present in all parts of North Africa, its mountains and deserts, the Saharan Atlas in Algeria, Ayru Azwad in Mali, as well as Niger and the plateaus Eastern, the High and Small Atlas, the desert and semi-desert regions of Morocco, the Mauritanian desert, and even the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean.[41]

Conclusion

This paper has attempted to shed light on graphization, the first step in the process of Amazigh language standardization. It has discussed in detail the history of the Tifinagh script, the basic strategies and approaches employed in its standardization, and evaluated its adequacy as a writing system based on Cooper.[42] As mentioned above, developing a script specific to Amazigh is a significant achievement in the language's revitalization process. It achieves two goals simultaneously. Thanks to Tifinagh, Amazigh has transitioned from an oral to a written status, promoting its presence in the linguistic market and enabling it to serve various functions across different domains. Furthermore, writing the Amazigh language in Tifinagh is a way to revive and protect this script. Moreover, Tifinagh represents not only a script but also an ambassador of the entire Amazigh identity at the global level.

References

Agnaou, Fatima. Curricula et manuels scolaires: pour quel aménagement linguistique de l’amazighe marocain?, Asinag3, 2009

Ameur, M., Bouhajar, A., Boukhris, F., Boukous, A., Boumalk,A., Mohamed Elmedloui, M., and Iazzi, Elmehdi E., Graphie et Orthographie de l’Amazighe. Rabat: Publications de l’Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe, Elmaarif Al Jadida, 2006.

Asndal, Ali. « اللغة الأمازيغية واشكالية حرف الكتابة ». Hespress, July 9, 2011. (https://www.hespress.com/A8-54886.html).

Assid, Ahmed. « في الذكرى 11 لترسيم أبجدية تيفيناغ ». Hespress, February 10, 2014. (https://www.hespress.com/8A159838.html).

Belqaçem, Mbarek. « لماذا الحرف اللاتيني هو الأنفع للأمازيغية؟ ». Hespress, June 20, 2012. (https://www.hespress.com/B2-3-92584.html).

Berry, Jack. "The Making of Alphabets." In Advances in the Creation and Revision of Writing Systems, edited by Joshua A. Fishman, 737-753. The Hague: Mouton, 1977.

Boukous, Ahmed. Revitalizing the Amazigh language: Stakes, challenges, and strategies. Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe, 2012.

Boukous, Ahmed. “The planning of Standardizing Amazigh language The Moroccan Experience.” Iles d Imesli, no. 6 (2014): 7-23.

Camps, Gabriel. Ecritures - Ecriture libyque. Encyclopédie berbère XVII, 1996, 2564-2573.

Camps, Gabriel. Recherches sur les plus anciennes inscriptions libyques de l’Afrique du Nord et du Sahara. Bulletin archéologique du CTHS, n.s., 10–11 (1978): 143-166.

Chaker, Salem. L'ECRITURE LIBYCO-BERBERE Etat des lieux et perspectives. Paris: Centre de Recherche Berbère, Inalco, 2011.

Chaker, Salem, and Slimane Hachi. A propos de l’origine et de l’âge de l’écriture libyco-berbère. Etudes berbères et chamito-sémitiques, Mélanges offerts à Karl-G. Prasse, edited by S. Chaker, 95-111. Paris/Louvain: Editions Peeters, 2000.

Cooper, Robert L. Language planning and social change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

El Guabli, Brahim. "(Re) Invention of Tradition, Subversive Memory, and Morocco's Re-Amazighization: From Erasure of Imazighen to the Performance of Tifinagh in Public Life." Expressions maghrébines 19, no. 1 (2020): 143-168.

Erraji, Mohamed. “عصيد: "تيفيناغ" انتقل من المنع السلطويّ إلى التوافق الوطنيّ.” Hespress, November 23, 2013. https://www.hespress.com/8a-149765.html

Galand, Lionel. Les alphabets libyques. Antiquités africaines 25 (1989) : 69-81.

Galand, Lionel. Un vieux débat : l’origine de l’écriture libyco-berbère. Lettre de l’Association des Amis de l’Art Rupestre Saharien 20 (2001): 21-24.

Haugen, Einar. Dialect, language, nation. American anthropologist 68, no. 4 (1966): 922-935.

Ichou, A., and S. Fathi. "Promoting Quality, Equality and Inclusion through Rethinking Mediums of Instruction in Moroccan Public Schools." International Journal of Language and Literary Studies 4, no. 2 (2022): 296-320.

Ichou, A., and S. Fathi. "Amazigh Language in Education Policy and Planning in Morocco: Effects of the Gap between Macro and Micro Levels of Planning." International Journal of Social Science And Human Research 5, no. 8 (2022): 3702-3719.

Ichou, A., and S. Fathi. "Effects of Language Stratification on Amazigh Functional Use in the Moroccan Language Market." Revue des Études Amazighes 6, no. 1 (2024): 85-104.

Ichou, A., and S. Fathi. "Enacting the Official Character of Amazigh Language in Morocco: Myth or Reality?" Journal of Applied Language and Culture Studies 8, no. 2 (2025): 142-158.

Kaplan, Robert B., and Richard B. Baldauf Jr. Language planning from practice to theory. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 1997.

Oussikoum, Saïd. L’enseignement de l’amazighe au Maroc: entre aspirations et contraintes. Revue des Études Amazighes 2, no. 1 (2018): 13-24.

Skounti, Ahmed. “كتابة اللغة الأمازيغية والدستور الجديد”. Hespress, June 25, 2011. (https://www.hespress.com/AF-53407.html).

Skounti, Ahmed, and Abdelhay Lemjidi. Tirra: aux origines de l'écriture au Maroc. Vol. 1. Institut royal de la culture amazighe, 2003.

[1] Robert. L. Cooper, Language planning and social change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

[2] Robert B .Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Language Planning from Practice to Theory (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 1997).

[3] Einar Haugen, “Dialect, language, nation”, American anthropologist 68 no.4 (1966): 929.

[4] Ahmed Boukous, Revitalizing the Amazigh language: Stakes, challenges, and strategies (Rabat: IRCAM, 2012), 211.

[5] Ahmed Boukous, Revitalizing the Amazigh language: Stakes, challenges, and strategies, 212.

[6] Ibid.

[7] These criteria are important for validating the adequacy of writing systems. Based on leading key figures in linguistics (Bloomfield 1942; Fishman 1970), Cooper (1989) divides them into two major criteria: psycholinguistic or technical and sociolinguistic.

[8]Ahmed Boukous, “The planning of Standardizing Amazigh language: The Moroccan Experience”, Iles d Imesli 6 (2014): 8.

[9] Meftaha Ameur, Aicha Bouhajar, Fatima Boukhris, Ahmed Boukous, Abdellah Boumalk, Mohamed Elmedloui, Elmehdi E. Iazzi, Graphie et Orthographie de l’Amazighe (Rabat : Publications de l’Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe, Elmaarif Al Jadida, 2006), 12.

[10] Ibid., 13.

[11] Ibid., 15.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., 16.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17]Ibid., 23.

[18] Ahmed Boukous, Revitalizing the Amazigh language: Stakes, challenges, and strategies, 216.

[19] Ibid., 214.

[20] Ibid., 215.

[21]Ibid., 216.

[22] Robert. L. Cooper, Language planning and social change, 126.

[23] Mbarek Belqaçem, « لماذا الحرف اللاتيني هو الأنفع للأمازيغية؟ », Hespress, June 20, 2012. https://www.hespress.com/B2-3-92584.html

[24]Ali Asndal, « اللغة الأمازيغية واشكالية حرف الكتابة », Hespress, July 9, 2011. https://www.hespress.com/A8-54886.html

[25] Ahmed Skounti, “كتابة اللغة الأمازيغية والدستور الجديد”, Hespress, June 25, 2011, https://www.hespress.com/AF-53407.html

[26] Mbarek Belqaçem, « لماذا الحرف اللاتيني هو الأنفع للأمازيغية؟ ».

[27] Brahim El Guabli, "(Re) Invention of Tradition, Subversive Memory, and Morocco's Re-Amazighization: From Erasure of Imazighen to the Performance of Tifinagh in Public Life," Expressions maghrébines 19, no. 1 (2020): 155.

[28] Mohamed Lahrouchi, “The Amazigh influence on Moroccan Arabic: Phonological and morphological borrowing,” The International Journal of Arabic Linguistics 4 no .1 (2018).

[29] These examples are adapted from Mbarek Belqaçem, « لماذا الحرف اللاتيني هو الأنفع للأمازيغية؟ ».

[30] These examples are adapted from Mbarek Belqaçem, « لماذا الحرف اللاتيني هو الأنفع للأمازيغية؟ ».

[31] These examples are adapted from Mbarek Belqaçem, « لماذا الحرف اللاتيني هو الأنفع للأمازيغية؟ ».

[32] Robert. L. Cooper, Language planning and social change, 126.

[33] Jack, Berry, “The Making of The Alphabets,” “Advances in the Creation and Revision of Writing Systems,” ed., Joshua A. Fishman (The Hague: Mouton, 1977)

[34] Robert. L. Cooper, Language planning and social change, 126.

[35] Ibid., 127.

[36] Ahmed Boukous, Revitalizing the Amazigh language: Stakes, challenges, and strategies, 216.

[37] Ibid., 219.

[38] Ahmed Skounti, “كتابة اللغة الأمازيغية والدستور الجديد”.

[39] Ahmed Assid, « في الذكرى 11 لترسيم أبجدية تيفيناغ », Hespress, February 10, 2014. https://www.hespress.com/8A159838.html

[40] Mohamed Erraji, “عصيد: "تيفيناغ" انتقل من المنع السلطويّ إلى التوافق الوطنيّ, ” Hespress, November 23, 2013. https://www.hespress.com/8a-149765.html

[41] Ahmed Skounti, “كتابة اللغة الأمازيغية والدستور الجديد”.

[42] Robert. L. Cooper. Language planning and social change.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 4 • Issue 1 • Fall 2025

Pages 52-67

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Hassan II University