Art Research and Tamazgha Futurity

Inhabiting the Desert

AUTHOR: Carlos Perez Marin

Inhabiting the Desert

Carlos Perez Marin

The inhabitants of the Sahara desert have developed multiple ways of adapting to their environment, creating specific habitats, always subordinate to nature (and to other factors and constraints). They have been doing so for centuries, imprinting their adaptive practice on different layers and scales of being in the desert. By decoding these spaces, we can better understand other architectures, seemingly unrelated to the desert, which today are considered World Heritage Sites in both Northern Africa and Southern Europe. Moreover, these traditional architectures, urban planning and territory planning could (should) be a model of contemporaneity for our cities and regions when we think about creating habitats that might confront new challenges: economic and social development, energy consumption, water resources optimisation, climate evolution adaptation...

The oases are probably the best example of true sustainable development, where inhabitants have been able to build with what they have around them, not just houses, not just villages, but a complete ecosystem that is a hybrid between agricultural and metropolitan areas. In this “oasian planning” everything is related and only a transdisciplinary approach can be used to understand the genesis and development of these habitable spaces in order to avoid the simplification of these complex artificial habitats, sometimes used to build false imagineries.

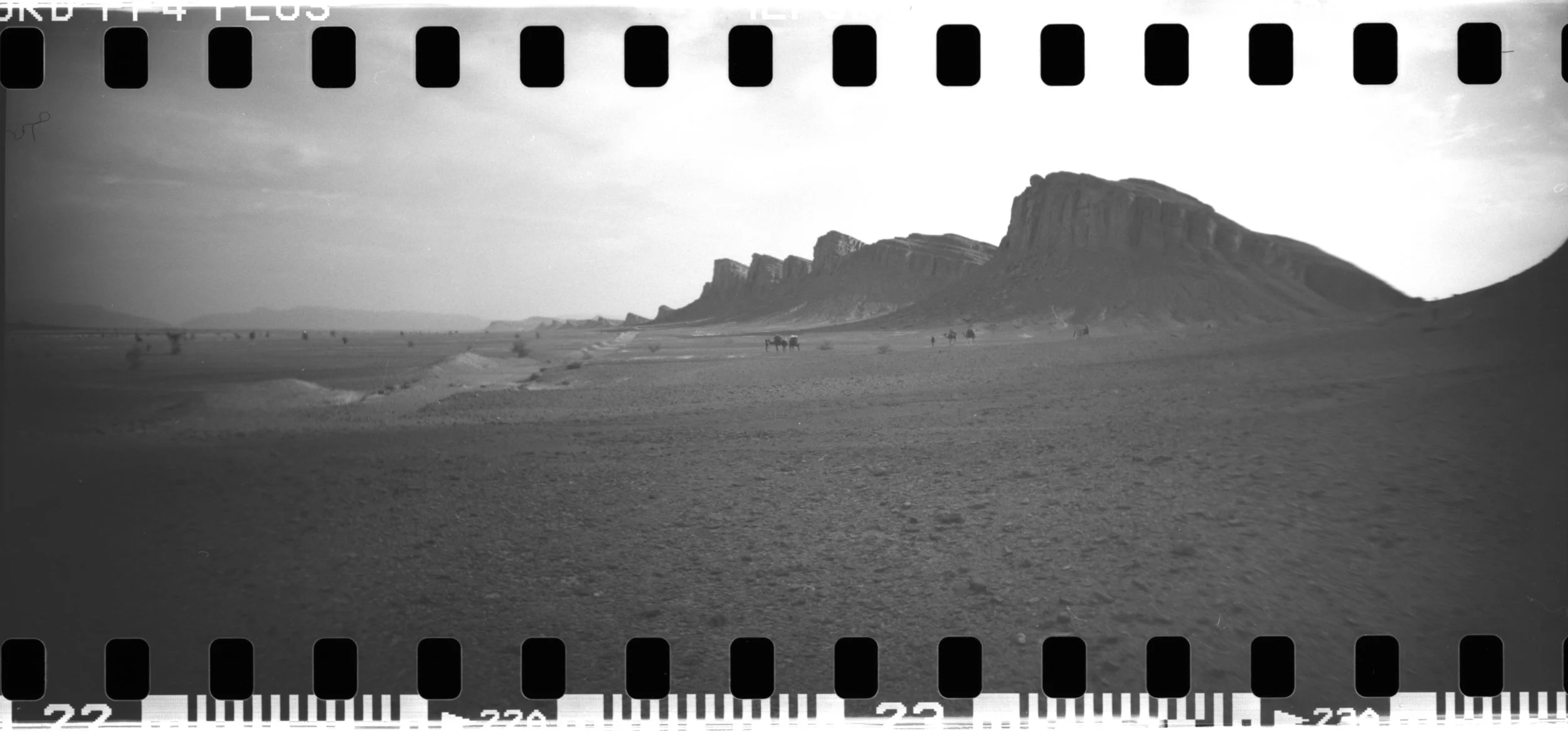

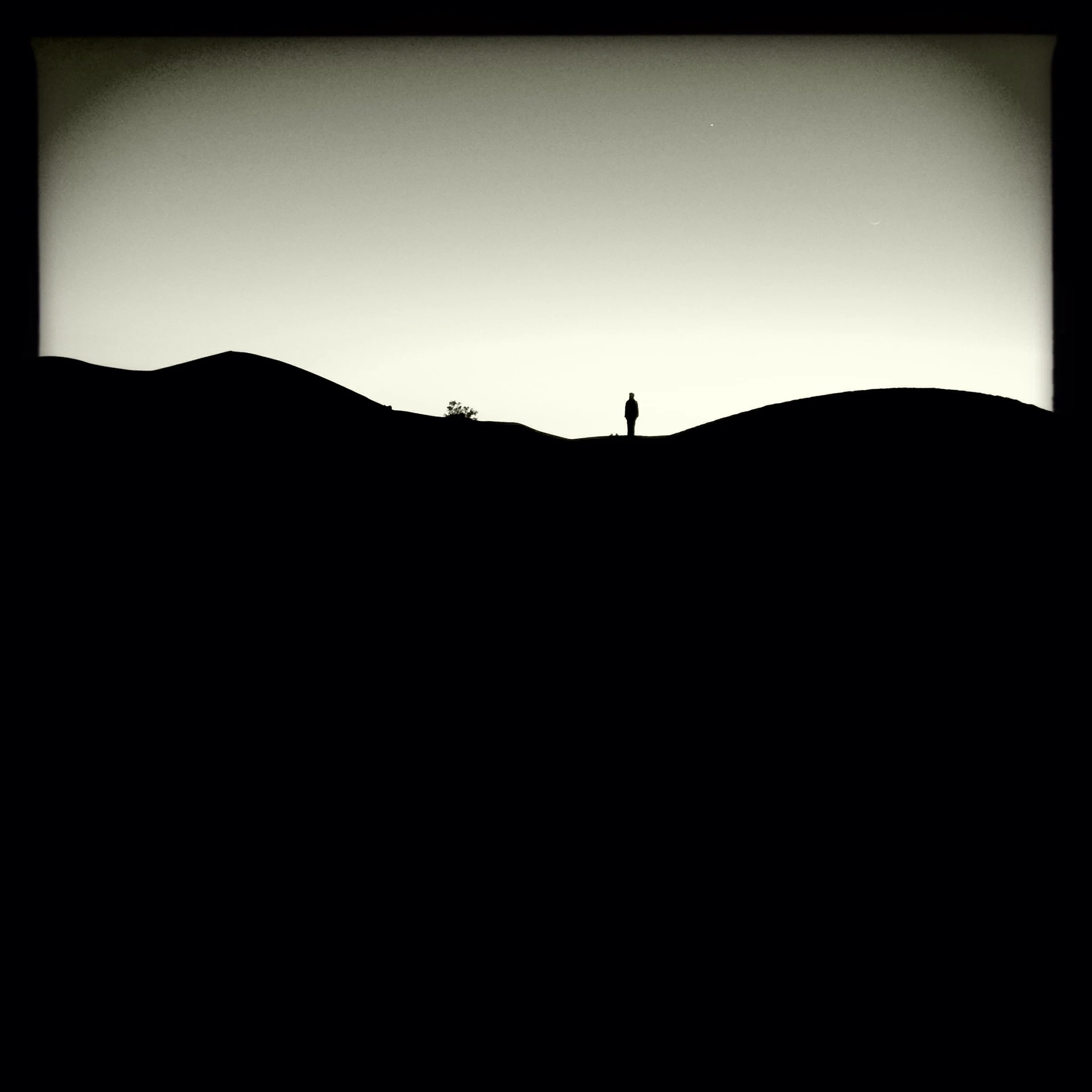

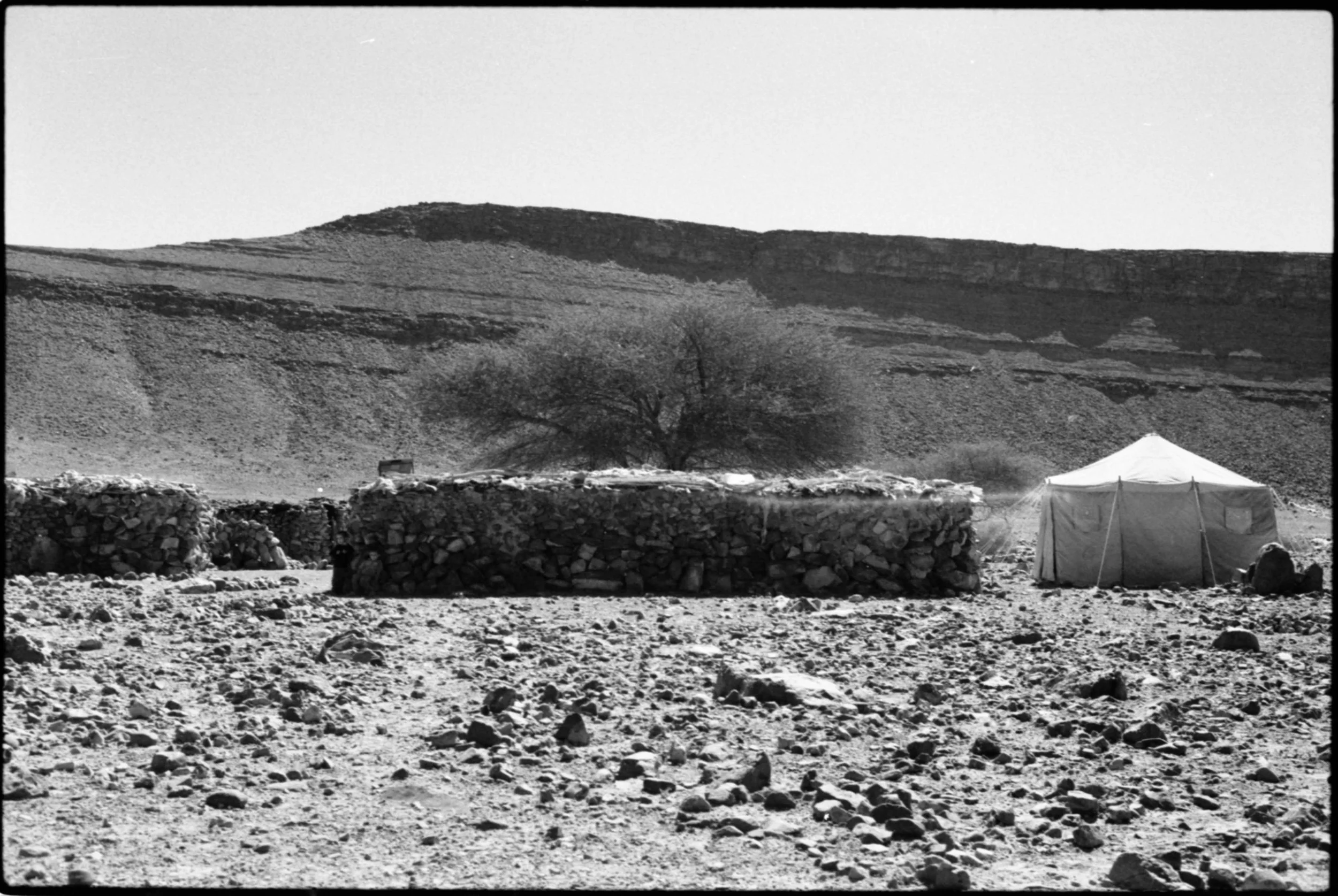

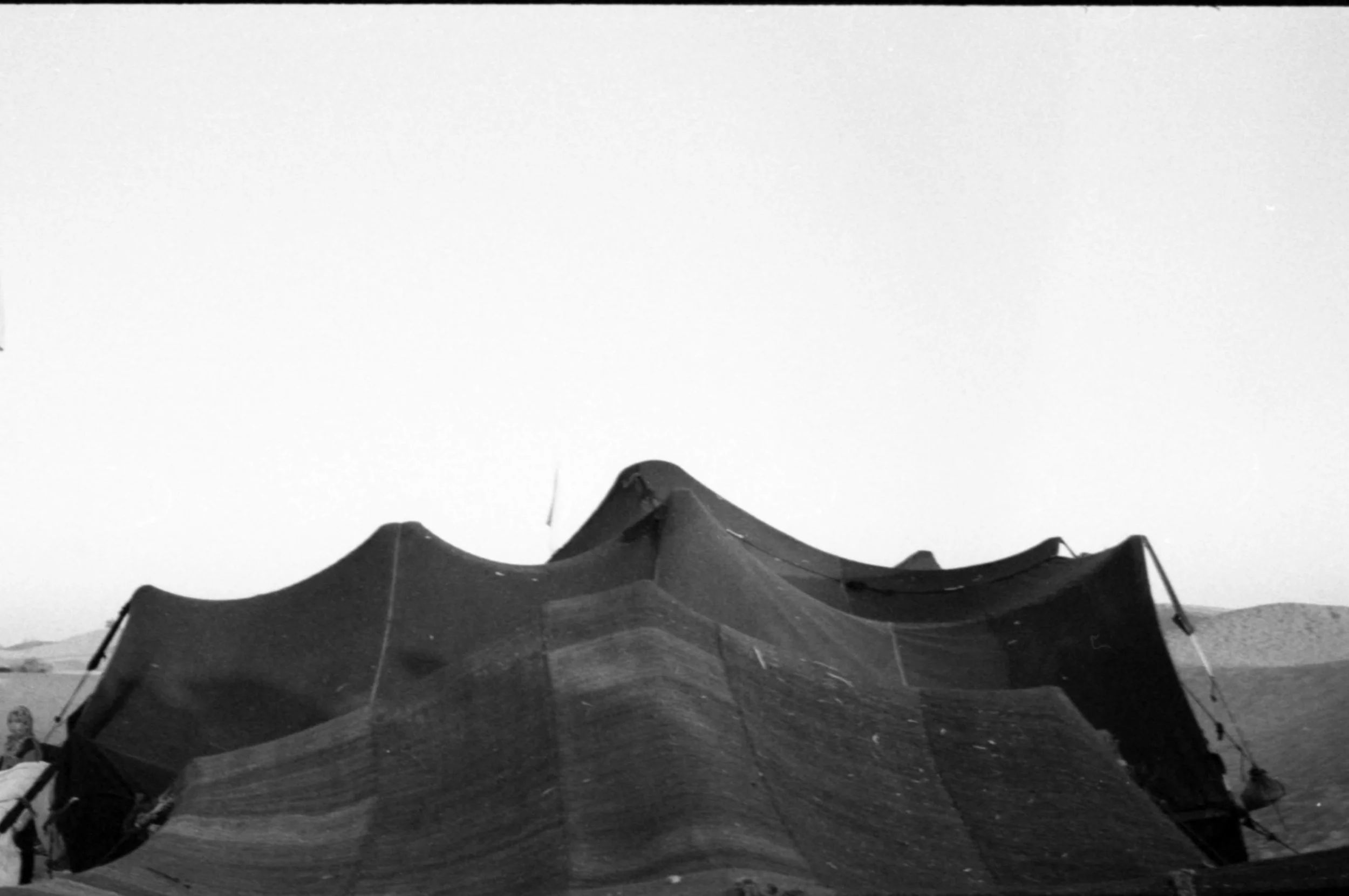

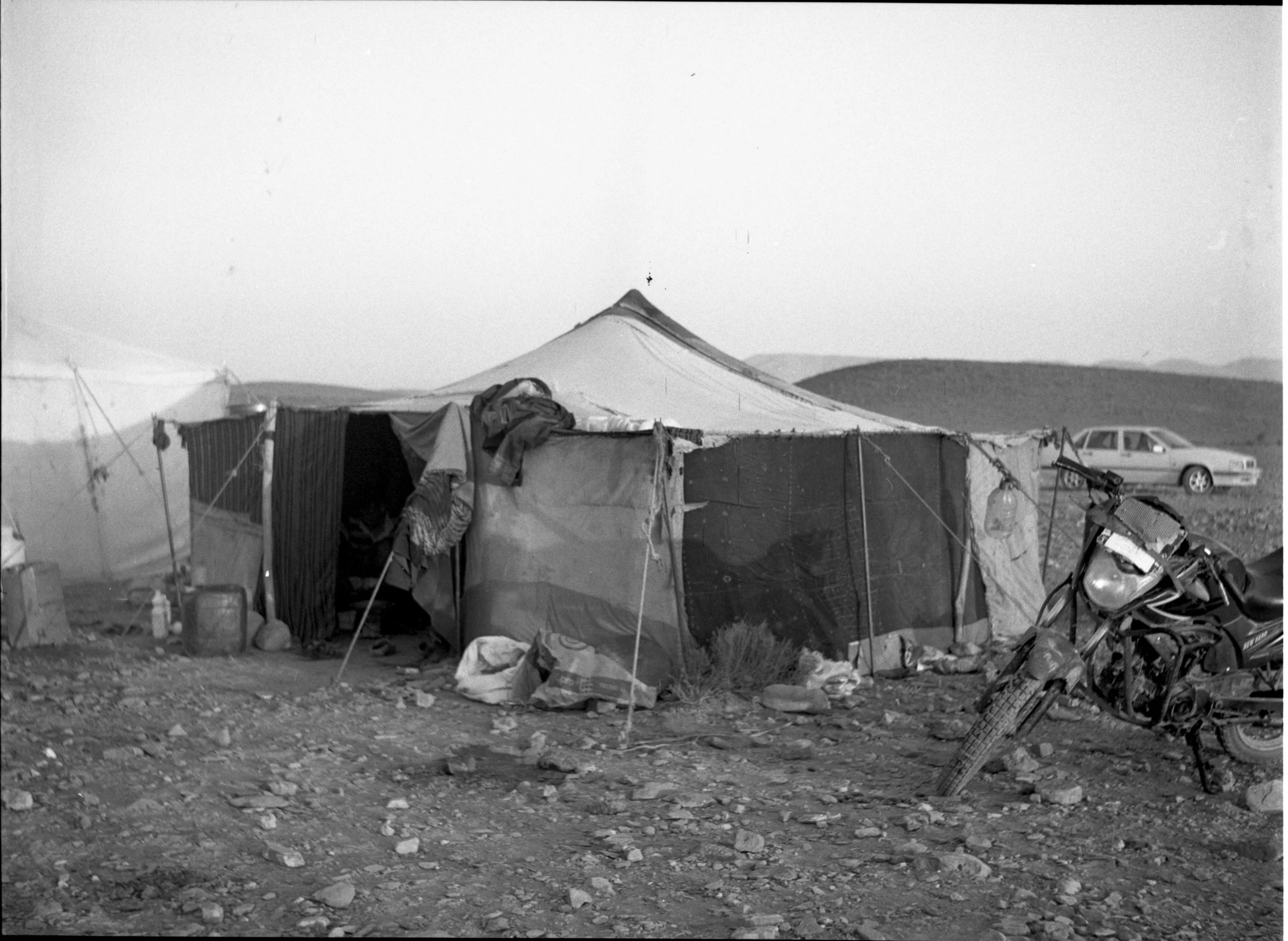

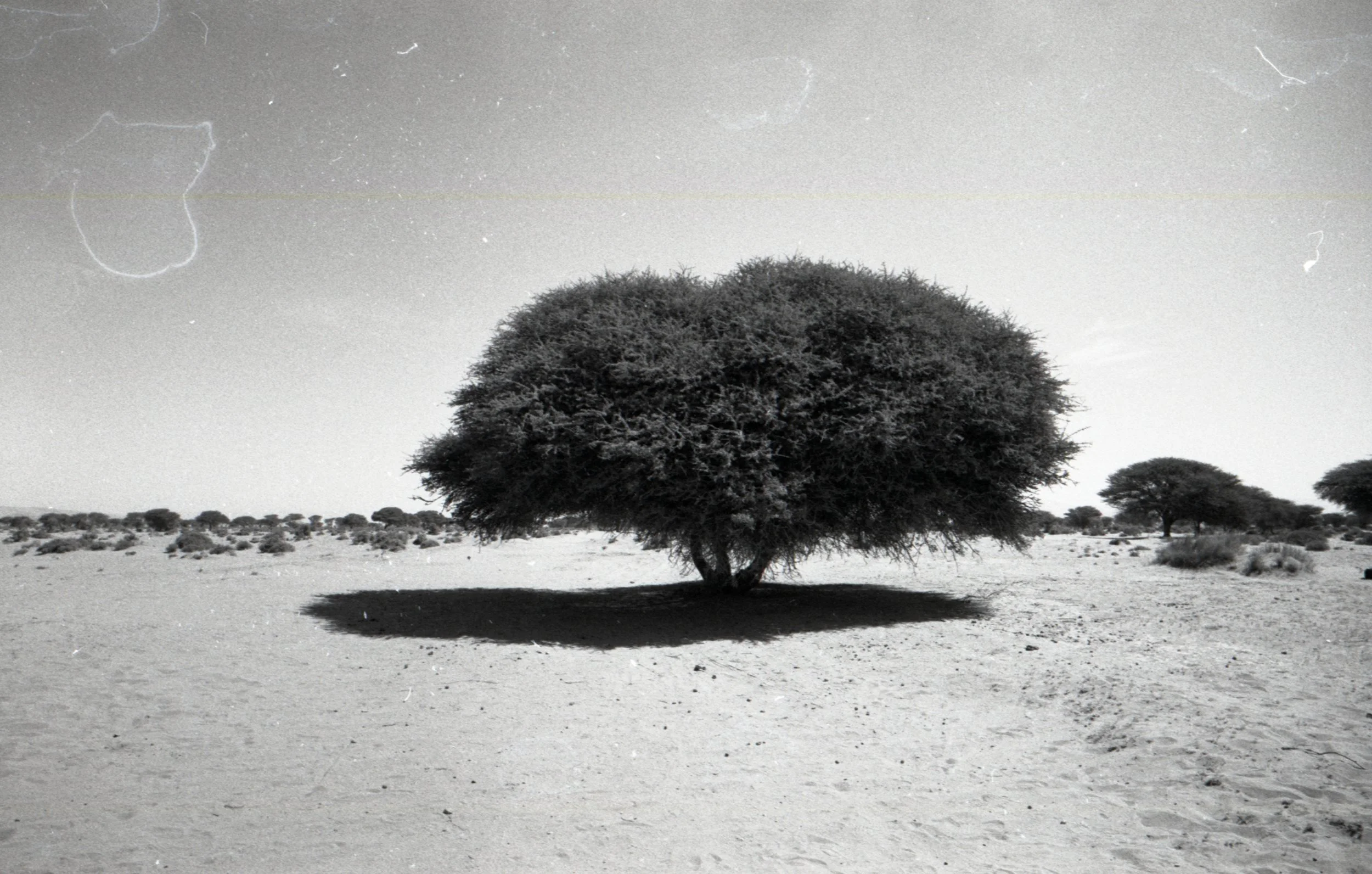

Outside the oases, there are also (temporary) habitats created by nomads with the few items they find or carry (animals often provide building materials). It is true that what was once considered the great nomadism (with movements between the High Atlas and the Senegal River) has almost disappeared in the western Sahara desert due to various factors: colonialism, droughts and armed conflict. Nowadays, nomadic camps are reduced to a few tents, whereas in the last century, they could consist of up to 400 units. The routes and campsites, as in the oases, are directly linked to the presence of water and whenever possible, shade, even if provided by a single tree (palm, acacia, tamarisk or taichot are the main trees in these regions).

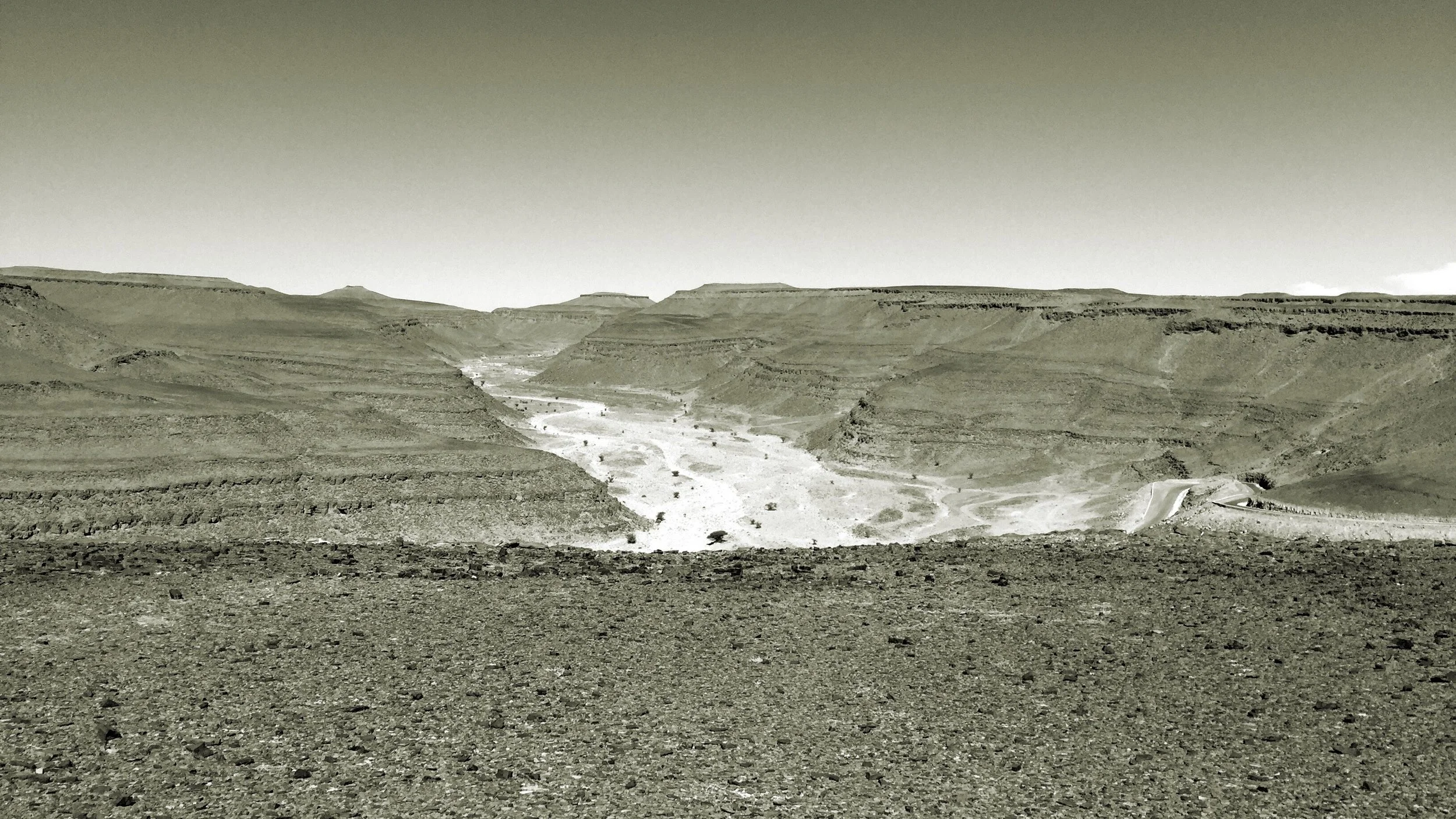

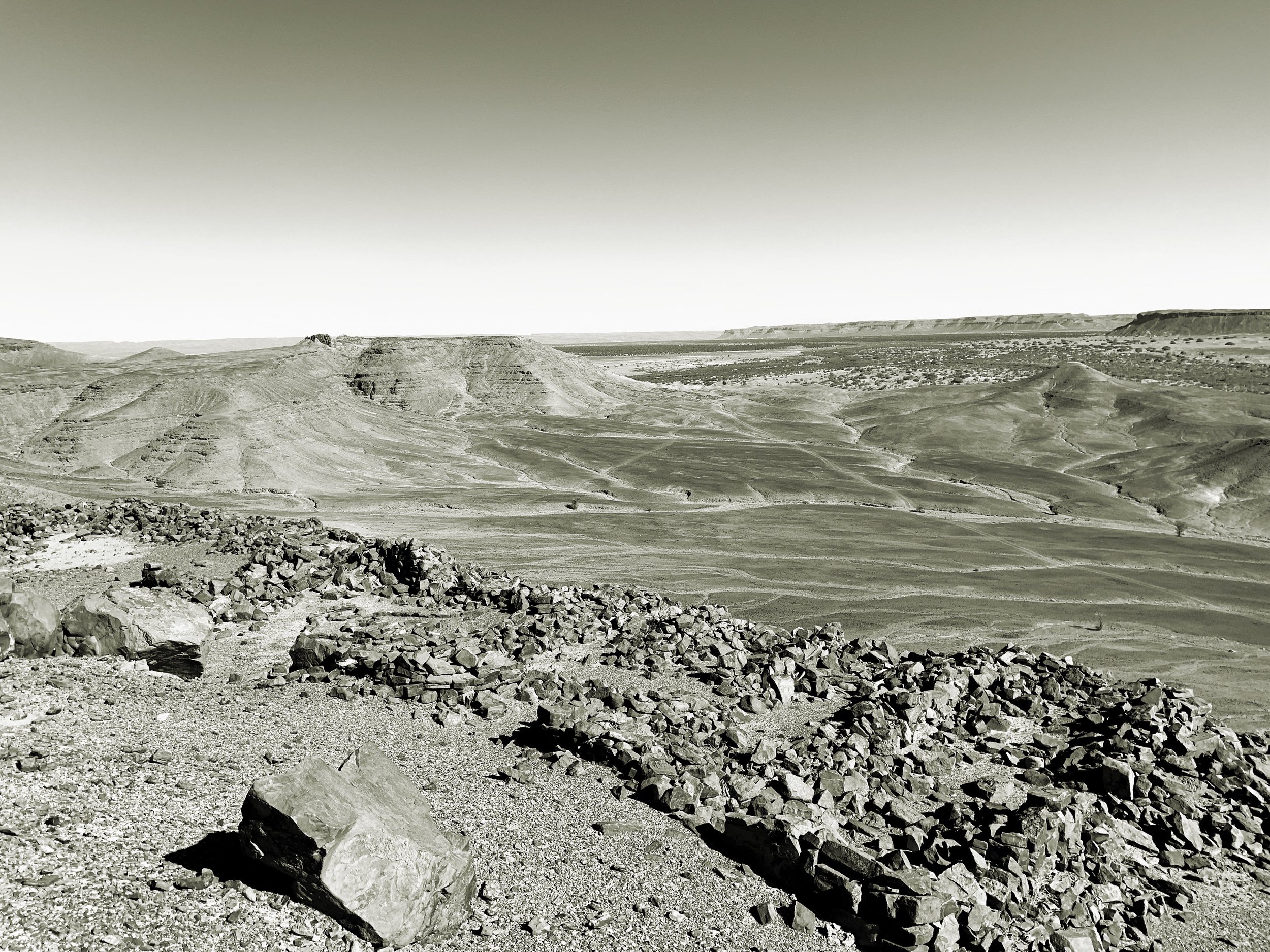

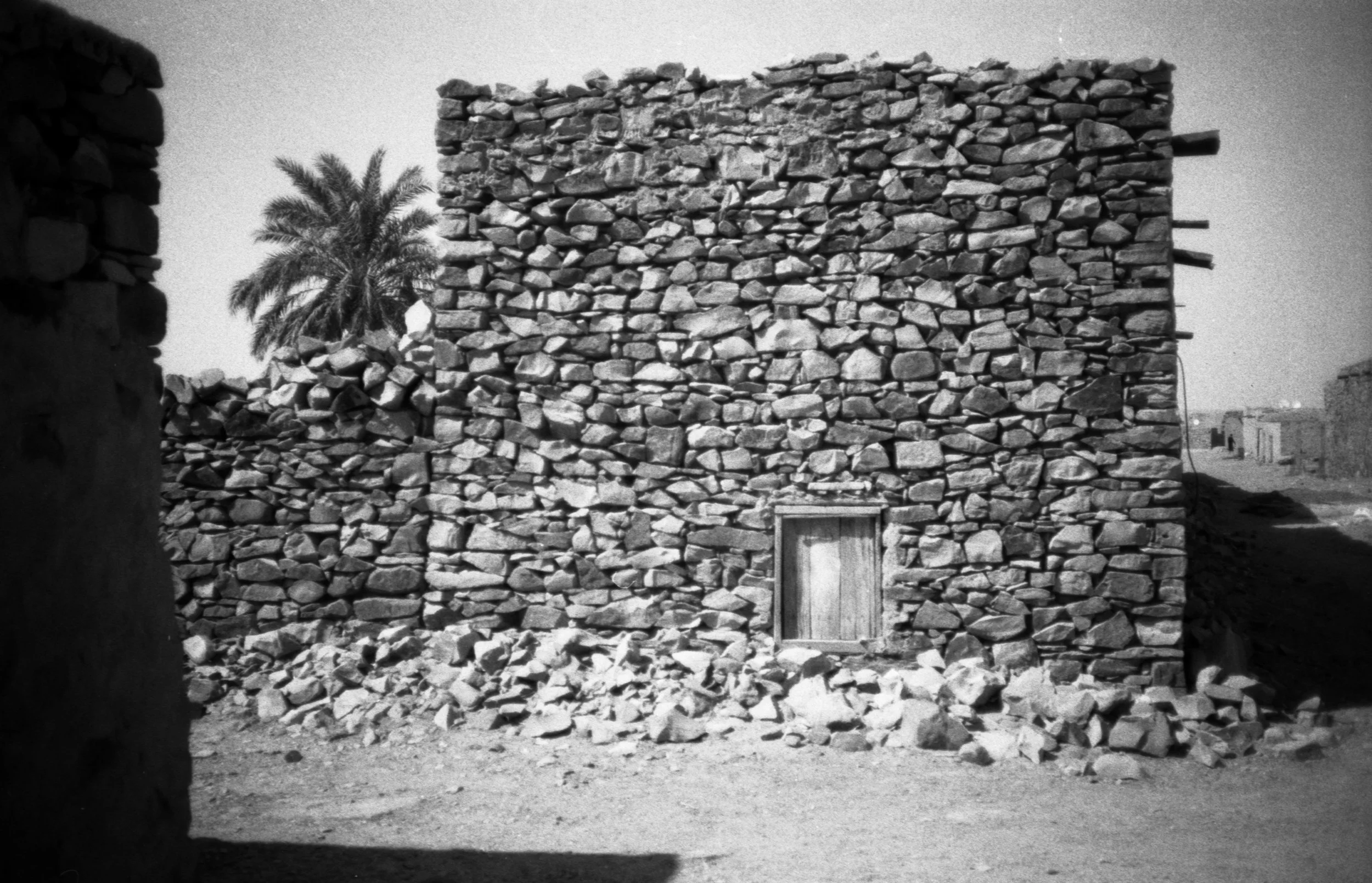

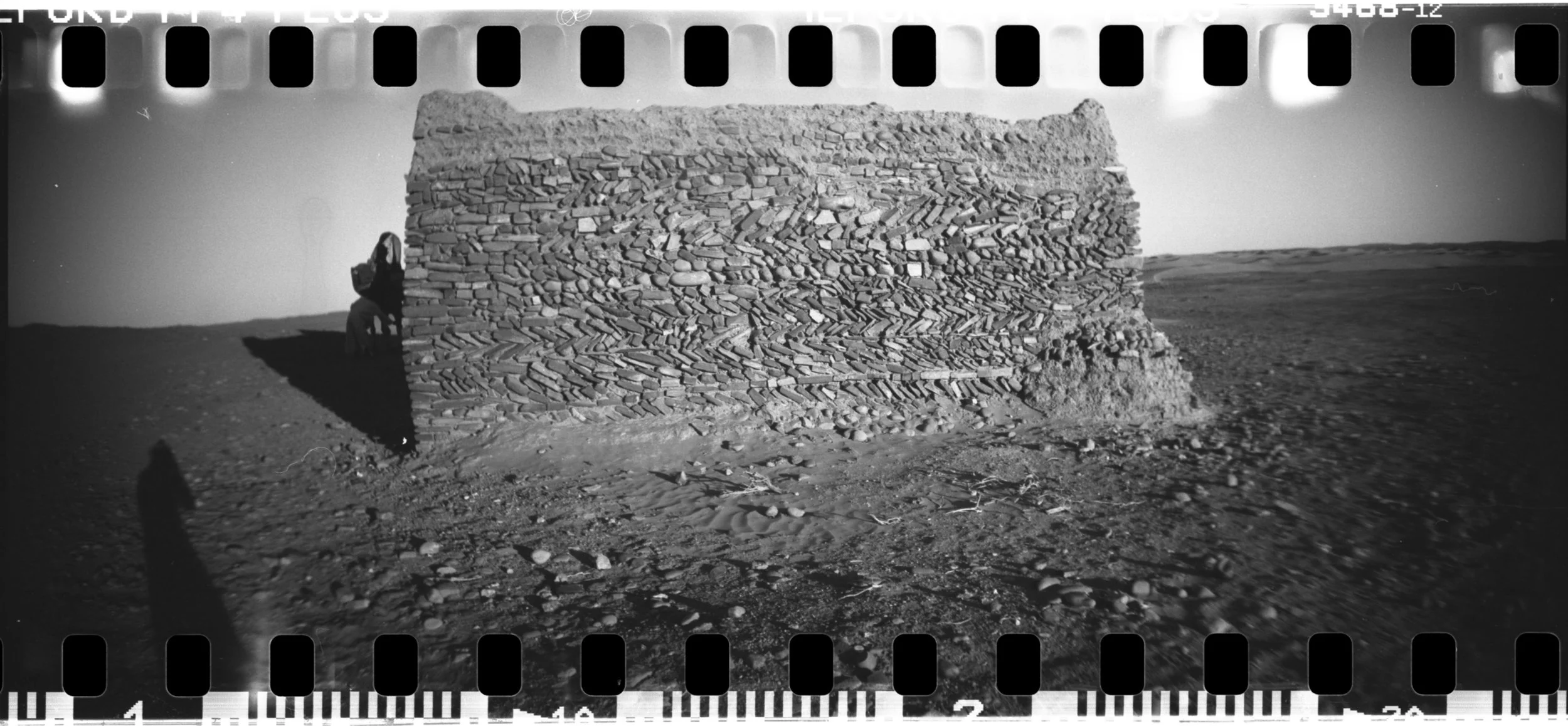

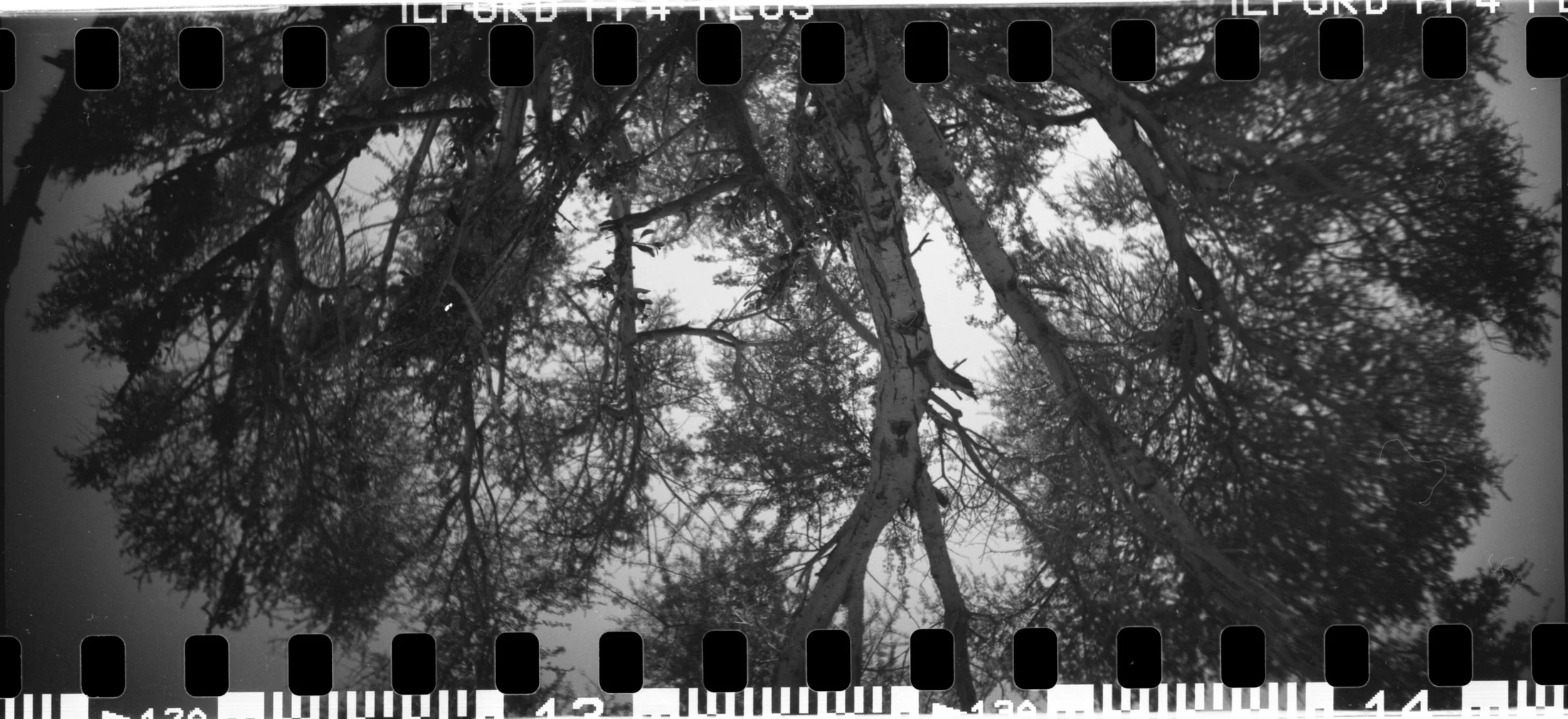

The following selection of photographs shows the evolution of habitats in different regions of the Sahara desert at its westernmost latitude, from oases (on both the northern and southern shores) to nomadic territories; at times using “traditional” building materials (rammed earth, stone, wood, wool…), at other times using intangible materials to create living spaces where there is no architecture. It is noticeable how nomadic habitats condition the sedentary architecture of the oases as a way of maintaining contact with nature.

This ongoing research has been carried out since 2010 through cultural activities, workshops, visits, conversations, observations, experiments, and experiences within the framework of various platforms created for this purpose such as Marsad Drâa, Caravane Tighmert, Project Qafila, and Caravane Ouadane (2021-2023), and resulted in a series of reflections translated into texts, photographs, drawings, lectures and interviews shared on carlosperezmarin.com.

Cameras used: iPhone 4, iPhone 5, iPhone 6, iPhone XS Max, iPhone 15 Pro Max, Lomokino, Sprocket Rocket, Lubitel 166 Universal, Olympus XA, Leica M6 and Bolex H16 SBM.

oases

1.0 valleys

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 4 • Issue 1 • Fall 2025

Pages 29-30

Language: English

1.1 oases

1.2 infrastructures

1.3 ksour and oases

1.4 ksour

1.5 ksour dwellings

1.6 kasbahs

1.7 oases dwellings

2. nomad territories

2.0 open spaces

2.1 oases

2.2 infrastructures

2.3 dwellings

2.4 temporary dwellings

2.5 tents

2.6 trees

2.7 rugs