Essays

Wandering minstrels and epic poetry from Morocco’s Berber Highlands

AUTHOR: Michael Peyron

Wandering Minstrels and Epic Poetry from Morocco’s Berber Highlands

Michael Peyron

Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane

Introduction

The purpose of this research note is to shed further light on types of epic tamaziɣt poetry as practiced by Sufi-inspired bards (imdyazn) from Morocco’s eastern highlands, the Fazaz area proper (Middle Atlas), and idurar n latlas axattar n šerq (Eastern High Atlas). The most famous imdyazn come from the Taarart valley and Zawit Si Hamza on the south slope of the mighty mountain Aari u-Ayyash, or from elsewhere in Ayt Yafelman country. The subject matter relates chiefly to anti-French resistance (1908-1936), together with more recent socio-political events, the style being predominantly engagé. The means of expression revolve around two ballad-style genres: tamdyazt and tayffart. However, poets sometimes resort to shorter pieces of the izli or tamawayt genre. Instruments used by imdyazn are the fiddle (lkamanža), tambourine (allun) and reed-flute (aɣanim).

Each group consists of a ššix and his companions (ireddadn), together with a flute player (bu wɣanim), the lynch-pin of the group, who doubles as a clown, thus bringing light relief to the bardic performance. Wherever they go in the Berber area they stage performances of their art in exchange of temporary board and lodging. Usually, the bu wɣanim scouts ahead to whichever village has been chosen for that particular night’s stop-over. He is the one who brings to the villagers (ayt iɣerman) glad tidings that minstrels are on the way; he also gets one of the well-heeled villagers to provide hospitality. When the minstrels arrive there is an elaborate ritual during which the bu wɣanim lies down and shams death until the rest of the group have arrived. He then resuscitates and they have dinner with their host, after which the minstrels start their show. This starts off with a series of short poems (izlan), after which come the much-expected ballads, the latest in their repertoire. Once the performance is over, a prolonged series of cathartic aḥidus-style dances, involving all villagers present, lasts well into the small hours.

The wandering minstrels are organized in small groups who travel through the highland area in summer to reach the hot Tadla plain where they will find temporary jobs as harvesters. However, when the first snows of autumn herald seasonal change, laden with gifts, the group head back towards their native turf, the iɣrem where their families await them.

1. Setting up a Tamdyazt

Amazigh epic poetry comes essentially in tayffart or tamdyazt form. These are lengthy poetic constructions, the result of intense memorization, consisting of forty or more couplets (tiwan). Occasionally, there is a three-line item known as a tamalayt.

In the opening line of the poem, or incipit, the bard usually invokes the Almighty, and a bevy of local tutelary saints. In a text-book tamdyazt the incipit reappears to round off the poem. A specific tiwent will be repeated as a refrain; in some cases one may observe two different refrains in the same tamdyazt.

In order to respect the underlying metric pattern, the vowels in certain words may be lengthened or shortened. For example, sidi ṛebbi > sidi ya ṛebbi; žud ɣifi > žud ɣiyifi; ku ywn > kun; ku yukk > kukk; ddunit > dduyt; ingr-i > igr-i, etc. Furthermore, tamaziɣt as spoken between the Fazaz and South-East Morocco features numerous lexical variants involving vowel and consonant change. Thus ɣurm > zarm; ur idd > wl idd; meš traram > meš tlalam; ttzawarm > dzawarm, items calculated to ensnare or puzzle researchers unfamiliar with such phonological niceties.

2. Timdyazin of the Resistance Period

A certain number of timdyazin appear in the present writer’s volume devoted to episodes of Amazigh resistance in the Atlas Mountains (2018), which undoubtedly witnessed the heyday of the genre. Among the better-known of these are: tamdyazt n imḥiwaš, tayyfart xef ben ɛumar, tamdyazt xf ayt ɛli w braḥim, tamdyazt xef lqayd n ḥeddu, ɛawd ay ils-inu mani zzi nebdu, tamdyazt n zayd u ḥmad, etc.

Arguably, however, the most famous ballads are those that deal with the bloody battle of Tazigzawt (ti n dzizawt) which raged throughout August and September 1932 around some wooded hills in the Eastern High Atlas between Tunfit and Aghbala, when some 1000 resistance fighters faced off two divisions of the French army. This event, the focus of the present writer’s research, was the subject of painstaking visits to this secluded spot (2005-2007), together with work on two ballads: tamdyazt xef tzizawt (Peyron, 2002) and tamdyazt n sidi lmekki.

The first, initially collected by Arsène Roux, was published in Poésies berbères de l’époque héroïque (Peyron & Roux 2002). A text-book tamdyazt by an unknown bard from Ayt Sukhman, the closing line repeats the incipit: a nnbi, a bu faḍma, ay awal iɣudan, a lɛezz w wawal; in the first seven tiwan the poet invokes God, Sidi Benasser, Sidi Driss and Sidi Lahbib. Few events are actually referred to and then only in a highly, moral tone. The mujahidin are depicted as unworthy beings who went to earth in caves and betrayed each other. Ultimately, it was not so much artillery bombardment as hunger that proved their undoing. Finally, they served as a feast for jackals: wellah! ay ifran nna ɣas tinḍlin agg ttuyrem / is txedmem i wuššen is iya tiɛiyyadin! ar tanggarutt yaḍer laẓ y imžuhad / amuttel magg insa l msakin t tiğğal. Miscellaneous izlan and timawayin, further describing these events, are attributed to the famous poetess Tawkhettalt from Tizi n-Isly, some of which have been published recently (Azergui, 2021).

The second tamdyazt, studied in detail by Jeanine Drouin (1975), Michael Peyron (2009) and Bassou Hamri (2011) consists of a no-holds-barred critique of Sidi Lmekki who, as resistance leader had sworn to fight till the end, only to cravenly surrender at the end of the day on Tazigzawt and meekly accept to become qayd of the ayt bužžur (Ayt Sukhman who had capitulated) at Aghbala under the French. Earlier, he had considered himself God’s instrument destined to fire the magic cartridge, bequeathed to him by his father – the famous Sidi Ali Amhawsh – which would guarantee victory over the irumin (inn-awn sidi lmekki tella ɣuri tadwatt iweṣṣa-yi baba…). But the din of the tragic battle still rings in his ears, as no U-Sukhman who passed by the Ashlu ravine on Tazigzawt will care to deny (ur sar š mi ttux, hatin illa wetn-nnem, a tazizawt, digi, / wenna yzra n ašlu ad ur iṣexṣar i w-sexman awal nna gan!). There is no dearth of material related to this event (see this writer’s Poésies berbères de l’époque héroïque, Maroc central (1908-1932) [2002], co-authored with Arsène Roux).

3. Contemporary Timdyazin

Ballads referred to as contemporary deal with the period 1980-2000, three of which appear in the author’s book on Berber poetry Isaffen Ghbanin (1993). The first is a famous piece: “Tell me, o my muse, of those far-off days!” (ara, ɛawd, ay imi, ssiwl magga zzman a!). It figured in the repertoire of Rwisha, the great Khenifra poet, around 1984. However, the actual lines are variously attributed either to Hammu u Lyazid, forerunner of the present strain of Fazaz Amazigh poetry, or to one of Rwisha’s song-writers, a certain Hammou u Lghazi.

This tamdyazt features a famous incipit: “With you do I commence, O Lord, send me inspiration /You that do possess what I desire, show me no favouritism!” (bdix-š, a sidi ya ṛebbi žud ɣifi /illa ɣurš uynna rix bla tudmawin). This verse harks back to a sort of foundation myth in which God created heaven and earth, rivers, mountains and plains, together with the living creatures that peopled that universe. The poem then deals with modern times where human behavior is censored, chiefly because of man’s materialistic, grasping attitude (ṭṭemɛ), the cause of so much misery and suffering.

These themes are further exploited by a bard from Ayt Yahya, the well-known Hmad Waqqa, in his tamdyazt “O Lord, plant my roots by an irrigation-ditch!” (ya ṛebbi siwḍ iẓeɣwran-inu tama n terwa), collected by my friend Fatima Kadiri during the Aïd el Arch ceremonies at Tunfit in March 1978.

In the opening tiwent the amdyaz launches into his critique of society: “Of the present time consider the impiety, let all remain with down-cast eye, / beware, the spoken word is like unto unburned wood!” (wa, texxa tsaɛt ttx, ku yiwn ḥuḍr diyun / han awal am ukššiḍ ayd iya!). He then criticizes ayt wulli, the well-off sheep-owners, as well as their offspring’s dissolute behavior. However, he admits that he must take precautions and not go beyond certain limits, if his poem is to remain acceptable to the ears of all members of the public: “I’m careful what I say in case my tongue slips!” (da ḥeḍḍux aqmyu, ggwedx ad iššeḍ awal diyi!). All the same, he ultimately overdoes things and is unable to finish his poem, being reduced to silence by an influential member of the audience after having stigmatized the young Tunfit bloods by comparing them to Jews!

A third poem was collected by Rkia Mountassir on a market-day in 1984. It begins thus: “Lord ‘tis thou that I do implore!” (šeyyin ay mi qqarx, a ṛebbi!). Here, though the tiwan are shorter, the overall poem runs to 72 couplets and features various phonetic devices and a rich lexicon, mingling pure Amazigh items with Arabic loan-words, without deviating from the metric pattern. As usual, the amdyaz censors the all-pervading ungodliness and materialism: “Since lying has become second nature to you, the cost of living has deteriorated. / The Almighty has reduced your flocks and herds, has devastated your harvests!” (zeggwis ar ttenfaqem tiḥllal, tedda ɣas i wnaqqeṣ d unneyzi. / d ar ax-isnaqqaṣ nnit lmal, ar ax-isnaqqaṣ unebdu!). There have also been blatant cases of land-grabbing, entire pastures being fenced off by wealthy stock-breeders. As a result, neither can shepherds frequent them, nor can wood-cutters go there (ur da diys isawaɣ umeksa, ula ɣurs nṣafṛ s uzeddam). Worse still, age-old practices, such as helping or entertaining your neighbour are henceforth neglected (yaɣul iḥrem ɣurun ummɛtaq, nemyabbay ɣas s lbeɣd iberdan!). Finally, the bard exhorts his people to break bread together, that deceit and may be banished from among them (taɣul nnɛamt da t ttemmešfam, mr idd i leɣḍeṛ yr-ax!).

Next is a tamdyazt by Haddu Baku, a native of Tikajwin, Ayt Hnini clan of the Ayt Yahya, which features a typical incipit: bdix-š, a sidi ya ṛebbi, žud ɣuri! This was recorded by the writer near Anefgu in May 1988 and describes the various afflictions that plague contemporary society: ɛawd ay imi yxub i ddunit!

The present writer also had access to two versions of another ballad, a very popular one in the years 1980-1990, attributed to the famous bard Zayd Lesieur (ššix lisiwr) from Ishishawn (Southern Ayt Yahya): one version collected by Moha Moukhliss and published in Tifawt (June/July 1994); the other, decoded by my student Rqiya Montassir from Zawit esh-Sheikh, being a remix of two versions: one given to me on a mini-cassette in Midelt in the autumn of 1983 by Hmad u Sharif (ayt ḥdiddu n imdɣas); the second an incomplete recording by Ftima Derqawi, handed to me by her husband Sidi Moh Azayyi of Asaka, near Tunfit (Ayt Yahya), winter 1984-1985.

This version contains several cases where the cesura splits a word in two (as in adday below), allowing one to glide smoothly from one line to the next. For example: han lexzin yix t yad dat-am, a / dday temmud taft-tin dat-nnem. Whereas this ballad deals with the usual themes (hard luck, poverty, social difficulties of various kinds), we find allusions to King Hassan II of Morocco who was then embroiled in a proxy war with the Algerian leader, Boumdienne. Accounts of battles in the Western Sahara may be heard daily on the ṛṛadyu.

Another feature is that of two different refrains, several times repeated throughout the poem: “A totally unknown path I did follow” (kkix d yan ubrid, ur ğğin t annix)… alternates with: “He who has intelligence knows of what I tell” (wenna ylan ixf issen mayd qqisx). Finally, the incipit > ad isk-bux, ya ṛebbi, zwuṛ-anneɣ is correctly repeated at the end of the tamdyazt.

Conclusion

The imdyazn are becoming somewhat thin on the ground now. Yet in the Eastern High Atlas a few survivors are still holding out: Moha Akuray from Tunfit; Hammou Ikli, ššix Hammu Khela and Zayd u Zerri (aka lisiwr), all of whom I met on various occasions (2019-2021). One of the drawbacks is the dearth of practiced flute-players (id bu wɣanim), essential protagonists of each minstrel group. At the most recent flute-players’ festival at Lhajb (Middle Atlas). there were only three left, although a couple of youngsters are reputed to be undergoing training. The best place to see imdyazn in action remains agdud n sidi ḥmad u lmeɣni (brides’ festival), held the end of August near Imilshil.

Appendix

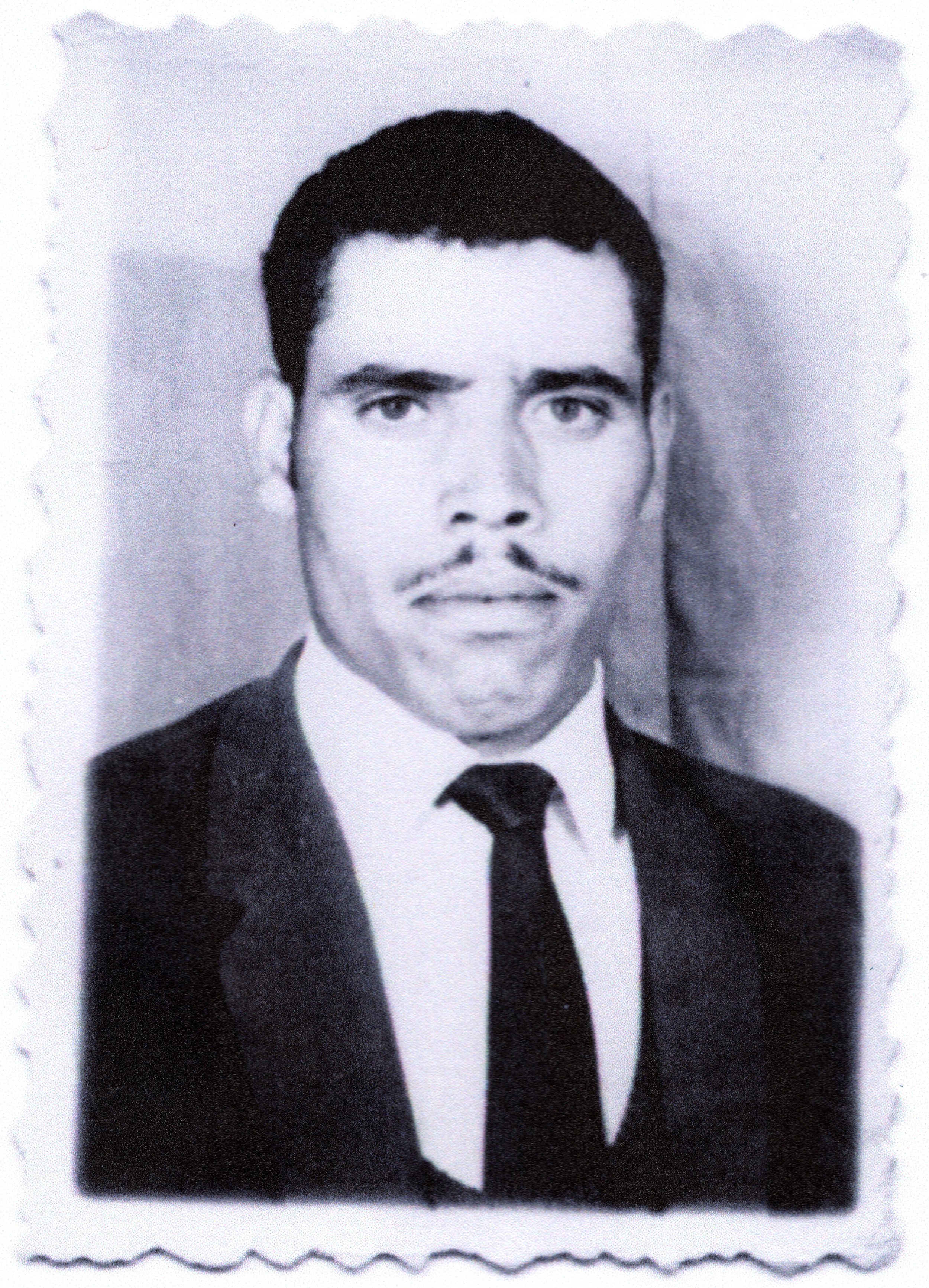

May 1974: Once, while travelling among the Ayt Sliman back of Jbel ‘Ayyashi, just beyond Tighermin at the ksar of Luggagh, I met a bu tallunt (tambourine-player) called Bassu ou Sekku, who used to accompany a wandering minstrel (amdyaz) called Moha u Lhussein u-Zahra (born 1934). In summer, so he told me, each one bearing a sickle, they would set out for the Tadla plain and seek employment as harvesters. Wherever they stopped for the night, they would entertain the master of the house with their music. This was the itinerary they usually followed:

1st day: Louggagh > Anefgu; 2nd day: Anefgu > Imilshil; 3rd day: Imilshil >Ighrem n-Ughbalou > Zerchan > Anergi; 4th day: Anergi > Tiffert n Ayt ‘Abdi; 5th day: Tiffert > Tagelft > Wawizaght.

From Wawizaght they would head down towards Fqih ben Salah or Beni Mellal to hire out their sickles to whoever was willing to take them on. Though the wages thus earned were not exceptionally high, it provided them with cash to buy provisions and whatever goodies for their families once they hit the homeward trail come September.

Bassu u Sekku (1974)

References

Arberry, Arthur John. 1969. Sufism: an account of the Mystics of Islam,

London: George Allen & Unwin.

Azergui, Aksil. 2021. Taougrat Oult Aissa et Taoukhetalt: deux poétesses de l’époque héroïque, Éd. CDL.

Boukhris, Fatima. 2014. “Bu uġanim, l’alter ego comique de l'amdyaz au Maroc central.” Études et Documents Berbéres 33: 159-170.

Bynon, James. 2017. Prose texts from the Ayt Hdiddu, Köln: Rudiger Verlag.

Drouin, Jeannine. 1975. Un cycle oral hagiographique dans le Moyen-Atlas marocain. Paris: Sorbonne.

Hamri, Basso. 2011. La poésie amazighe de l’Atlas central marocain. Rabat: IRCAM.

Jouad, Hassan. 1989.“Les Imdayzen, une voix de l’intellectualité rurale.” Les Prédicateurs profanes au Maghreb. Aix-en-Provence: Édisud.

_____. 1995, Le calcul inconscient de l’improvisation. Paris-Louvain: Peeters.

Khadaoui, Ali. 2005. “L’histoire de la résistance armée dans les Atlas ‘racontée par la poésie’.” Tawiza 95.

Khettouch, Haddou. 2005. La mauvaise gestion de la cité perçue par un genre littéraire: cas de timdyazin. Thèse de Doctorat, Faculté des Lettres, Dhar el Mahraz: Fès.

Peyron, Michael. 1993. Isaffen Ghbanin/Rivières profondes, Casablanca, Wallada.

_____. 2007. “Oralité et résistance : dits poétiques et non poétiques ayant pour thème le siège du Tazizaout (Haut Atlas marocain, 1932) », Études & Documents Berbères, 25-26: 307-316.

_____. 2010. “Le rôle politico-social des imdyazn du Haut Atlas oriental,” Available at : http://michaelpeyron.unblog.fr/2010/06/21/le-role-politico-sociale-des-imdyazn-du-haut-atlas-oriental.

_____. 2018. Tradition orale et résistance amazighe dans l'Atlas marocain (1912-1936), Köln: Rudiger Verlag.

Roux, Arsène. 1928. “Les ‘Imdyazen’ ou aèdes berbères.” Hespéris, 2e trim.

Roux, Arsène & Michael Peyron. 2002. Poésies berbères de l’époque héroïque, Maroc central (1908-1932). Aix-en-Provence: Édisud.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 1 • Issue 1 • Fall 2023

Pages 153-158

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane